Description

In her book, Chrusciel maps the biblical event of annunciation onto the current migration crises. Annunciation becomes a symbol of the “yes” that we utter in front of reality, particularly confronted with exiles, strangers—in other words, the other. The book quivers on the brink between openness to the other and the terror the other brings out in us. What does it mean to say “yes” to a stranger? What implications, threats, blessings and responsibilities do “yes” carry? Can we say “yes” to a dislocated soul in order to become more fully who we were meant to be?

Through prayer, lament, and lullaby Chrusciel attempts to give voice to the voiceless and find healing in what seems to be an insurmountable rift of dislocation.

This new collection of poems by Ewa Chrusciel gives astonishing attention to the migrants in our world. For those who love translation, these poems read as if half-original, half-version, just as they should, being both becalmed and capsized in spirit. Transparent sea-swells carry the [submerged cries of humanity. This poet is a marvel at hearing and finding beauty where there is no good.

Fanny Howe, author of The Needle’s Eye: Passing through Youth

The condition of displacement has never been so widespread, or so misunderstood. In her hard-hitting new volume, Ewa Chrusciel weaves together the rich narratives of refugees across several continents, and – with great tenderness – gives us a way to hear the ‘rain inside their breathing’. Through the familiar contours of tradition, she also finds a new, transcendent language that embraces the lengths and limits of our humanity; words that teach us ‘to bless, to wound’. Against fear, against loss, Chrusciel writes: ‘We walk on eggs, / we tap on earth’. We read and follow in her steps.

Theophilus Kwek, Winner of the New Poets’ Prize, 2016; Editor, Oxford Press

Reading the poetry of Ewa Chrusciel is like listening in the dark to the dark and familiar vowels of the stranger, the suppliant, the Pilgrim, the immigrant, the homeless, the stateless, the refugee, the walking trees, the Other. That’s how you discover that the Other is just a mirror-hyperbole where the virtues and the fears of the Self are projected. Because migration is an integral part of the human adventure on earth, as old as humanity, religion and poetry.

Gazmend Kapllani, author of Short Border Handbook

About the Author

Reviews

Excerpt

Ewa Chrusciel is a bilingual poet and a translator. Her two previous books in English are Contraband of Hoopoe (Omnidawn, 2014) and Strata (Emergency Press, 2011). She has also published three books in Polish: Tobo?ek (2016), Sopi?ki (2009), Furkot (2001).

Her poems have appeared in numerous journals and anthologies in the US, Italy, and Poland, such as Boston Review, Jubilat, Colorado Review, Laurel Review, Spoon River Revie, Solstice, Il Giornale, and La Freccia et Il Cerchio. She is an associate professor of creative writing and poetry at Colby-Sawyer College in New Hampshire.

A brief interview with Ewa Chrusciel

(conducted by Rusty Morrison)

In OF ANNUNCIATIONS, you are navigating such difficult, complex subject matter—these include immigration, the mythic, the use if iconic figures, and more. You, yourself, bring the experience of an immigrant to this work, since you have lived this role. And you wrote so powerfully about it in CONTRABAND OF HOOPOE. But here, you are speaking in many voices, and of many voices that are beyond your own. Could you reflect on the risks of this? How you navigate those risks? How the necessity of this work evolved from the early poems you had written In order to act as witness, and to bring to that act a full admission of your own culpability—there is so much that must be kept in equipoise, even as there is never a simple equilibrium to achieve, never a simple balance possible between the positions of observer and observed, especially since one is never unified in any positioning, no position is ever fixed. I would be grateful to hear you speak to any of these issues. I know you have thought long about them.

I believe poetry is inhabited by many voices, and poets serve as midwives helping these voices out. (These voices might also belong to canaries singing in the mines.) In my new book, speaking in voices felt particularly pertinent because, via these poems, I wanted to reenact the pain of a migrant/refugee, as well as the curiosity and fear of a settler (another voice in my book).

The book has voices of migrants, non-migrants, settlers, volunteers (those who help migrants), a Syrian Boy, the mother of the Syrian boy, dybbuks, Guardian Angels, Archangels, Mother Guadalupe. I hope, however, that these voices are not to be understood as dramatic persona poems (like in Browning’s “My Last Duchess,” just to mention one example of a dramatic monologue). I, rather, meant these voices to be emblematic—the incarnations of our times, the embodiments of some kind of vision or conflict. Some of these voices represent forces rather than people. This is why I did not want to develop most of these voices into robust, solid characters, since they exist to articulate the dilemma of our times. Here the balance was the challenge. How to keep these voices as emblems of our times and to eschew simplifying the politics? How to exalt the human situation and yet manage to eschew the ideologies? In other words, how to tiptoe between the ideologies which may seek to claim the work for their own purposes? How to eschew writing poems that would be just a political response in anticipation of a political problem? By deliberately shifting the speakers’ positions, creating bewilderment (the one Fanny Howe elaborated on in her essay under the same name) via a “provisionality” of voices (as you said in your question acutely – “no position is ever fixed”) and a fluctuation of these voices (to convey the oscillation between openness towards “the other” and the fear), I was hoping to raise some questions without providing any ideological answers. Poetry is very different from politics; it thrives on ambiguity and curiosity. It can pose questions, without providing answers (not because poets are anarchists or are wishy-washy but because they don’t claim to know the answers to the mystery of beauty, violence, and suffering).

Via these bewildered and bewilderment-causing voices, I hoped to seek empathy with one other person or a family in crisis without taking an ideological view. By creating voices I wanted to highlight individual stories, since anything beyond the creation of a relationship between one person and one other (or several ‘ones other’) could fall into the crevice of ideology.

What is the risk involved in all this? The risk is – of misrepresentation and sentimentalization. How not to domesticate these voices; how to keep them wild? How to be of witness without exploiting somebody’s suffering by writing poetry about it; without having an agenda? How can language become a source of renewal without sentimentalizing somebody’s experience or falling into stereotypes and clichés?

Can you speak to the ways that the dybbuk came into this work. How did that figure emerge, and how did its emergence impact the trajectory of the work. And, since it’s always fascinating to consider the path that a writer chooses not to take, and how that path still provides a ghosting presence in a work—could you speak about how you chose to remove the figure of the ibbur from the poems, yet how its presence is still palpable?

When you grow up in Poland, where history, literature, and culture are neatly intertwined with Jewish history and culture, you find yourself wondering about dybbuks. In high school I was fascinated by Hanna Krall’s journalism in which there were stories of dybbuks, among others (her focus was Holocaust). Just to clarify, in Jewish mysticism and folklore, a dybbuk is the displaced soul of a dead person. It is popularly believed to be a “clinging spirit”—a disturbed soul that possesses us. Such a spirit that seeks revenge or justice is juxtaposed in Jewish Kabbalah with an ibbur, a benevolent, temporary, and at times voluntary possession. I removed ibbur from my book because I wanted to redefine and recuperate dybbuk by merging its characteristics with ibbur. Revault D’Allonnes’ Musical Variations on Jewish Thought gave me this idea for the complication of the binary between dybbuk and ibbur. For D’Allonnes, the dybbuk does not seek revenge, but rather social justice. “If the community wants to get rid of it … that is because it disturbs the social order,” D’Allones writes. In my book, the dybbuk desires to exist until its conflict is resolved and therefore it sneaks into the body (of a settler on non-migrant or a volunteer) in order to fulfill its mission. In that sense I wanted to resolve my own question: What becomes of the souls of drowned refugees who float in the water, without a burial? In my book these souls become various voices (of our conscience?) that inhabit us; they become good dybbuks.

I’d be grateful if you chose a point in the manuscript—perhaps a section of particularly powerful significance for you, or that was especially difficult for you—and then discuss why. What experience or convergence of experiences initiated any particular aspect of this work that might be fruitful to speak of? What did the writing of that part of the manuscript demand of you? Change in you? And/or you might focus part of the book that surprised you or frightened you because of what it demanded from you.

The writing of this book demanded from me that I strip the personal layer and transition from the personal story of failed “annunciation” to the public story of migrants. Some poems in the book: “Migrant woman Dreams of Love,” “Out of Archangel’s lungs,” “Within each migrant, a canticle” still carry the traces of my personal & failed love story. Because in my personal life, I first said yes to a stranger and then switched to no (out of fear and scandal), causing havoc, I chose the title “Of Annunciations.” In the Biblical scene Archangel Gabriel announces to Mary that she will become the Mother of God. Mary responds to the visitor: “Be it Done According to Thy Word.” The Archangel represents the other, a stranger in whom Mary trusts. My personal story was that of a failed annunciation. First, I was interested in the poems that would help me relive the trauma and heal, perhaps. However, with time I erased these personal poems, as I became more interested in mapping this biblical event onto the migration crises of this current historical moment, in which settlers and volunteers (as I call them in the book) encounter the strangers, refugees, migrants. My intention was also to symbolize the term further, as well as to stretch its connotations. Annunciation becomes a symbol of the “yes” that we utter in front of reality, particularly confronted with the exiles, strangers—in other words, the other.

Stripping of the personal in favor of the collective led not only to the convergence of these experiences, but the recuperation of the personal through the collective. By the way, it might be of some significance that the word exile comes from Greek word xeniteia (xenos, a stranger), which for the monks of late antiquity actually meant something positive. It was a yearning for a spiritual detachment (often by leaving your land or your family) in order to be transformed and reach new spiritual orientation. In both Greek and Jewish culture there was a tradition of welcoming a stranger as if God entered your home. Ironically, the same root: “xenos” gave rise to the word “xenophobia.” For me writing this book meant going through the various stages of the origins of the word xeniteia. Detaching myself from the personal and embracing the collective was transformative. It was a good exile.

But when I transitioned from the personal to the collective, there were new challenges lurking—the risk of idealizing the migrants, the fear of becoming “simplifyingly” political or to exploit. The question that has been lingering is: “How to convey the drama of the migration crises without the simplification? How to also exalt the human condition – the human desire, the waves of hope and yearning of migrants who might end up in a society that does not really welcome them, but merely pretends to so as to look good to itself. To address this issue, there are poems in this book written from the point of view of settlers and non-migrants that sentimentalize or “exoticize” the migrants.

Would you tell me a bit about yourself? Anything about you that is not in the bio printed in the book, and that might give insight into your more personal relationship to this text?

I feel nomadic in my life, even though I have my places of belonging. I often pack and unpack and carry my luggage from one airport to another. Being an immigrant, I have also experienced what it feels like to be treated with a certain suspicion or superiority. I cannot take anything for granted. And there is always the dybbuk of the Polish language, which lies dormant under the layers of English accruing in me. Edward Said writes beautifully about this condition of internal exile in his essay “Reflections on Exile.” He says that the condition of exile is to never feel placid or self-satisfied. I think this is a human condition. We – humans – are exiles. We are uprooted. Poetry often speaks of “uprootedness.” Words are exiles and migrants; they cross borders and break the barriers. (And then, birds are migrants. I feel I belong when I see birds). Poetry speaks of a thirst, restlessness, and bewilderment. But it also helps us to re-create reality, especially if the “original” reality has hurt us. In that sense it can restore a sense of belonging. It can heal by constantly ripping the wound open. Poetry is like living with an open wound and this is paradoxically healing because we become real; we become true to ourselves. Hence, my personal relationship to this text.

I know you can’t list them all! But on first thought, on impulse, can you answer: Who are a couple or a few of the authors, artists, thinkers, workers (in any mediums) with whom you feel a kinship? Who/What comes to mind, just at this moment: who are you reading, listening to, looking at, watching, visiting currently? (You could say something about some of them, if you’d like, which makes this more alive for our readers.)

I just read Fanny Howe’s The Needle’s Eye which is a work of empathy and an incredible work of mappings (from St Francis to Tsarnaev Brothers just to mention one puzzling mapping). I also just discovered Eliza Griswold’s poetry and journalism. She travelled to Lampedusa and wrote about migration crises. She also travelled to Afghanistan to collect Landays, an ancient form of poetry which originated among nomads but now is often used by Afghan women. As Griswold explains “each [landay] has twenty-two syllables: nine in the first line, thirteen in the second. The poem ends with the sound “ma” or “na.” Sometimes they rhyme, but more often not.” The best landays thrive on ambiguity. I am just starting reading Griswold’s poems, and, I am very moved by what I have heard and read so far.

I have been also struck by Ocean Vuong’s poem. They are raw, nostalgic, unafraid of recuperating clichés.

Then, I always return to An Interrupted Life. Letters From Westerbork by Etty Hillesum. These are letters from the Holocaust by a young Jewish woman who manages to live with inner beauty and radiance within the brutal reality of the camp.

And finally, I could not put down The Corpse Exhibition and Other Stories of Iraq by Hassan Blasim. These short stories were realistic, violent, and yet fantastical.

I have also recently seen and shared with my students some documentaries and films about refugees. “Fire at Sea” an unusual and award-winning Italian documentary without narration (more like a book than a film) about the migration crises, directed by Gianfranco Rosi. The film was shot on Lampedusa in Sicily and follows two protagonist: a 12-year old boy from a local fishing family and a doctor who attends to migrants on their arrival. The title refers to a wartime Sicilian song about the bombing of an Italian warship in 1943 in port at Lampedusa, and how the flames lit up the night: Che fuoco a mare che c’è stasera (“What fire at sea there is tonight”).

Another documentary I have seen now several times, On the Bride’s Side (Io Sono Con La Sposa), very much inspired some of the poems in my book. It is an Italian–Palestinian unconventional road movie, which documents a smuggling expedition of 3,000 kilometers during four days in the lives of five Palestinian and Syrians who fled the war in Syria and, in the disguise of the wedding crew, are attempting to cross from Milan to Sweden. The film is being shot while they are being smuggled. The film won Balkan New Film Festival in 2015.

And finally Emanuele Crialese’s Terra Ferma. The film will leave you speechless; it fully conveys the drama of the refugees and local inhabitants of Lampedusa.

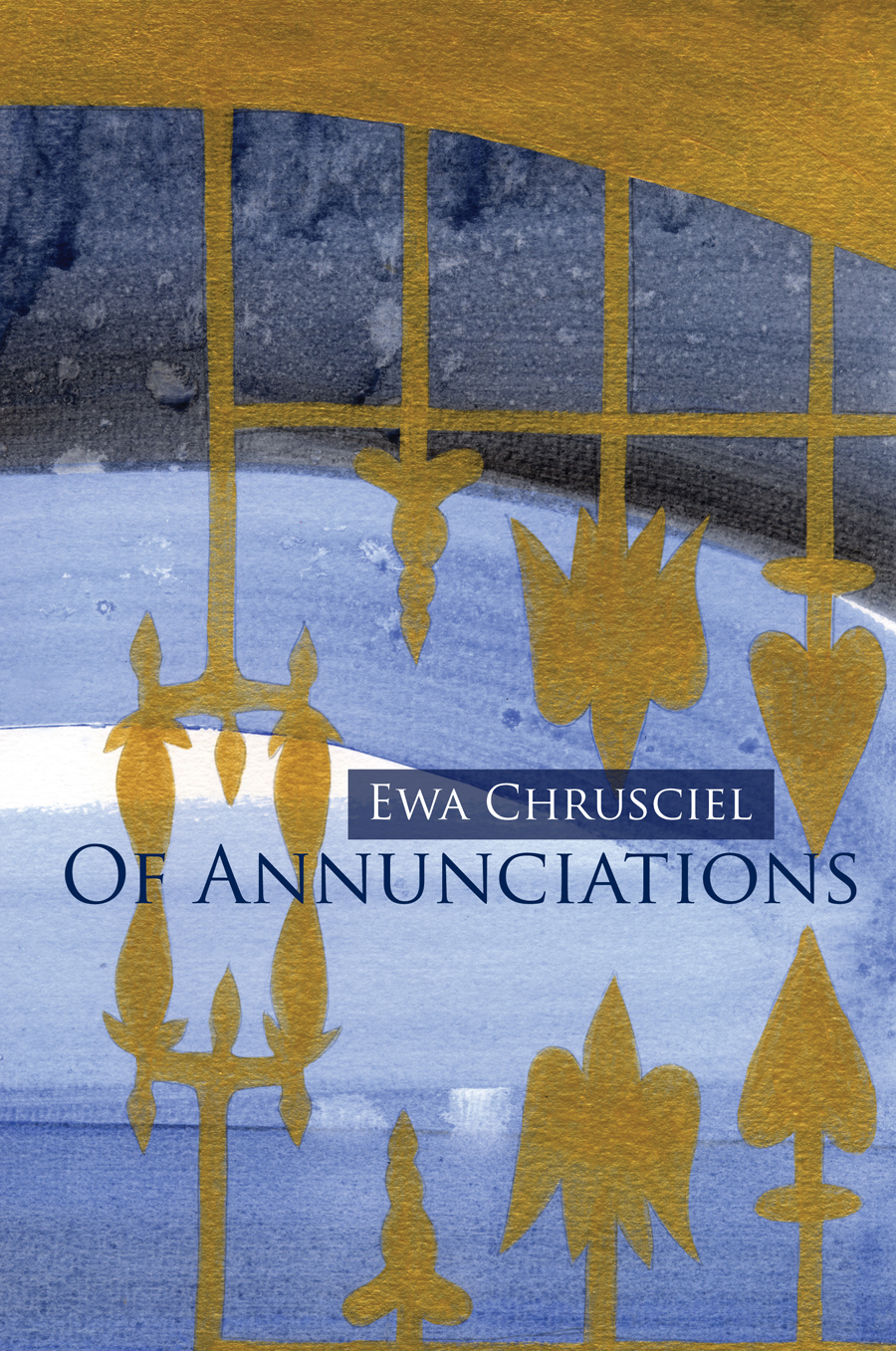

You selected the cover image for this book, could you speak to the artist’s work (whom you chose) and to the relevance of this image to this text?

“The Cloudmapping” by Julie Puttgen comes from a collaborative project of such complexity that only directing you to this website will do it justice. As Julie told me, this project was “a way for her friend Stephanie (aka JS van Buskirk, aka her childhood best friend) to approach her migration towards passing from this world, and for Julie to approach her migration towards losing her. Stephanie was already quite ill with a brain tumor when the project began; she died a few months after the project first opened in a gallery in ATL.”

For me, the cover is symbolic as there is boundless layered water and the golden – somewhat evanescent and elusive – gate-like image which also could look like Archangel Gabriel appearing to Mary. I very much liked that ambiguity and implied symbolism.

Chrusciel poses philosophical questions throughout the text, such as ‘Do souls have a language?’ and ‘What is the loon that descends/ us into silences?’ Her poems operate where the borders between self and other give way to a larger cosmic, perhaps more spiritual, truth.

Of Annunciations by Ewa Chrusciel maps the biblical event of annunciation onto the current migration crises. Chrusciel’s series of prayers, laments, and lullabies quivers on the brink between openness to the other and the terror the other brings out in us.”?

Polish immigrant Ewa Chrusciel is the author of two previous poetry collections in English: “Contraband of Hoopoe” and “Strata.” Omnidawn Publishing has just released her latest collection, “Of Annunciations.” The poems explore current migration crises throughout the world. She courageously exposes the migration crisis by using the image of a “dybbuk,” a figure from Jewish mysticism and folklore. The dybbuk is an invasive figure and surfaces as the persistent spirit of the dead who seek not revenge but fulfillment as they burrow into the heart of the living community.

[Chrusciel] speaks for the dead with a voice both clearer and more intimate than any I’ve read since Carolyn Forché’s The Country Between Us. Like Forché, Chrusciel does not turn the pain of others into a metaphor for her own pain. The language is direct and demanding . . . It is a testament to Chrusciel’s capacity for inscribing genuine empathy into her work that, although she foregrounds a metaphysical apparatus, she does so without stumbling.

This is an incredibly powerful collection of poems that strike with such beauty. Moving through poems both lyric and documentary, Chrusciel writes of those displaced by war, including those across Europe, connecting stories in the news to those scattered across history, and connecting a variety of displacements across multiple borders, traumas and losses.

Like to-do lists left out on the path of the pilgrim the poems in Ewa Chrusciel’s Of Annunciations are filled with starting points and stilled-time, rest stops and made-to-order dreams–a sort of story after a sort of story that lights a psychic lantern on our collective past—all the flawed and the half-felt, what’s been fled from and mightily dealt, as well as these personal totems that are not only self-animated but stumped for, lent to mythologies of a different nature altogether, and function as metaphysical staples and check-points, stymieing the imagination with their near-mystical conceits. . . . [T]hese missives are continuously infused with those songs long-thought-gone in which we are implored to share the earth’s gifts with those seeking to lend it their own indispensable notes.

Migrants’ Annunciation

Stones in our mouths,

barefoot we climb

rocks. We walk on eggs;

we tap the earth.

Each foot chants dust

we swallow. Our mouth, granular,

sealed. Our feet rock away

from crucifixions.

These rocks were feathers first—

magma and birds into earth,

charcoal lines, into waiting

shifting, memory

flicks red. Pilgrims, we

follow a spirit

of mountain up to a cross.

Blood trickles out of our mouths.

We stare into the lines of sacrifice.

The boat sways,

we comb our hair.