Description

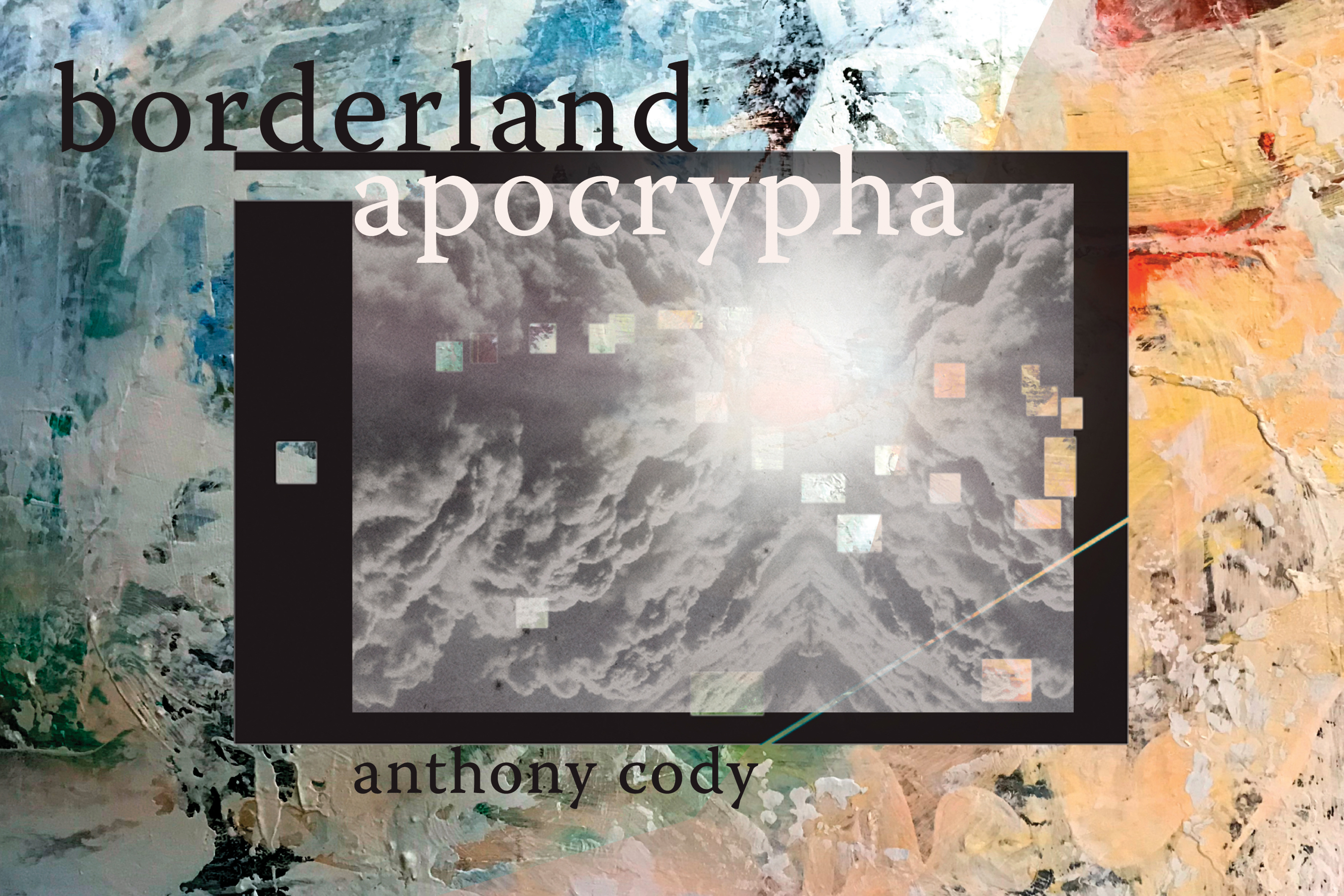

The 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo marked an end to the Mexican—American War, but it sparked a series of lynchings of Mexicans and subsequent erasures, and long-lasting traumas. This pattern of state-sanctioned violence committed towards communities of color continues to the present day. Borderland Apocrypha centers around the collective histories of these terrors, excavating the traumas born of turbulence at borderlands. In this debut collection, Anthony Cody responds to the destabilized, hostile landscapes and silenced histories of borderlands. His experimental poetic reinvents itself and shapeshifts in both form and space across the margin, the page, and the book in forms of resistance, signaling a reclamation and a re-occupation of what has been omitted. The poems ask the reader to engage in searching through the nested and cascading series of poems centered around familial and communal histories, structural racism, and natural ecosystems of borderlands. Relentless in its explorations, this collection shows how the past continues to inform actions, policies, and perceptions in North and Central America.

Rather than a proposal for re-imagining the US/Mexico border, Cody’s collection is an avant-garde examination of how borderlands have remained occupied spaces, and of the necessity of liberation to usher the earth and its people toward healing. Part auto-historia, part docu-poetic, part visual monument, part myth-making, Borderland Apocrypha unearths history in order to work toward survival, reckoning, and the building of a future that both acknowledges and moves on from tragedies of the past.

Borderland Apocrypha won Omnidawn’s 2018 Open Book Prize.

Intense feeling, empathy, rage, compassion swerves language, torques the page. History and data inflict. Intelligence composes, sequence wrestles with violence. It must be witnessed, expressed. The love is expression. Witness is form.

–Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Judge of the Open, author of Hello, the Roses

History’s true story is littered with collusions, silences, and with bodies: the dark ecology Anthony Cody brilliantly prosecutes in his debut collection, Borderland Apocrypha.

This book creates a new mechanism of critique through its forensic and conspiratorial speaker who gathers the dearth of evidence left behind by imperialism’s worse offenders and parses out a thrilling and trenchant document on the U.S. West’s legacy anti-Mexican bigotry. “The inheritance of the elsewhere is a cave of collapse,” writes Cody in a collection that will change the way we think about recovering histories.

Carmen Giménez-Smith

Because the document is always part of poetry in the general sense Shelley wrote about. Because the concept never did exceed politics or position. Because everything must change. Because the unaccountable, the disavowed, the apocryphal are the only metadata you’ll find in our nudes. Because whiteness is an extractive enterprise. Because patriarchy would look us in the face and think we’ll keep its secrets. Because with this history we’re not trying to accept the choice between having been colonizer or colonized. Because who, if we’re embraced or estranged from whiteness to suit whiteness, would hear us among the racial orders? Because vigilance committees now have Facebook groups, publicly funded military-grade weapons and surveillance technologies. Because our bodies are monetized in private prisons and in political speech. Because we’re not trying to confuse our faces with our masks. Because from the formal exigencies of document and concept, Anthony Cody delivers poetry back to the general sense of ritual and charm, a gnosis that takes its shape at the double edge of the words and the transmitting body. And because everything must change, the transit leads from here to the dead and back.

Farid Matuk

Read Cody’s investigations, these beyond-poems, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo of 1848, Mexican Indian lands, the untold occupations of America — as if you are hanging on that open-air killing tree. Notice the vortex of existence, yours, ours, the trapezoids of punishments, the dotted lines and splattered shapes of skin-text and the searing howls cut down the middle of the word bodies, usurpation, rape and theft bursting across the emptiness pages, terminations and exiles pinned on the Race Grid. Open these scrolls and peer at half-humanity America cutting you down, dangling — there is no wall after all, just a mirror of executions, “reach for the hand of a friend” “in a dream”, you are the “savage captured,” the “KickingSingingKickingSinging chant”, you are the segmented ink-jitters on Cody’s pages, you are the “atomic” Brown radiating yourself out of the 1850’s into this present of border mania. Read Cody ’s script, like no other — a photo-zoom of tragic roots and revelations, cartographies of “power and control,” and the transcendence of innocent bodies, somehow — American soul. Cody presents what has not been revealed, what must be said. This one-of-a-kind-book settles all cases against all border-crossers. It is possible: a brave, bold syntax, an unseen intelligence of ourselves, a new America. Bravo for these compassionate and brutal time-spaces, this brisling land voice— an exemplar of a bursting literature. Everything starts over now.

Juan Felipe Herrera

Focused on immigration, detention, and survival around the U.S.-Mexico border, Cody’s fierce, righteously outraged collection deserves shelf space near other recent monuments of highly political, partly conceptual poetry: M. NourBese Philips’s Zong!, for example, or Layli Long Soldier’s Whereas… Find in the course of Borderland Apocrypha’s built-up prepositions and propositions, “How it is to feel yourself less // how nothing goes numb.”

Stephanie Burt, American Poets Magazine

A beautifully designed book, the text is printed in landscape orientation, pushing against the boundaries of the page… Cody tells of personal history and family trauma. Setting poems amid the historical context of the lynching of Mexicans in the United States throughout the nineteenth century, he offers readers insight into a moment that has often been excluded from American history. He uses images to capture these moments in more than just words, creating an interactive space for deep engagement by deconstructing sentences and historical information… Cody makes his reader face what has been forgotten and swept under the rug, pushing our understanding of history—and also, importantly, our understanding of how books might evolve—to reflect our modern, multimodal forms of communication.

Apocryphal writings may be fictional or they may contain privileged knowledge known only to a few. Anthony Cody’s debut, Borderland Apocrypha, a National Book Award finalist, utilizes both—vivid imaginings and newly illuminated historical material—as a way to explore erased and overlooked violence against Mexicans in the United States, dating back to 1848 and resonating throughout the present. Visual, conceptual, and genre-defying, Cody’s work makes meaning and metaphor not just from language but from diagrams, photos, idea maps, and blank space, such that a poem lineated in regular stanzas feels like an aberration.

Emily Pérez, RHINO Magazine

Reviews

About the Author

Interview

Anthony Cody is a CantoMundo fellow from Fresno, California. His poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Gulf Coast, Ninth Letter, Prairie Schooner, TriQuarterly, The Boiler, among other journals. Anthony is a member of the Hmong American Writers’ Circle where he co-edited How Do I Begin?: A Hmong American Literary Anthology. As an MFA candidate at Fresno State, he serves as a fellow in the Laureate Lab Visual Wordist Studio started by Juan Felipe Herrera. He is a 2020 Desert Nights, Rising Stars Fellow. In 2018, he received the Galway Kinnell Scholarship to attend the Community of Writers. He is the communications manager for CantoMundo, as well as an associate poetry editor for Noemi Press.

An interview with Anthony Cody

(Conducted for Poets & Writers)

Inspiration: Being in community with other poets, writers, and artists. The act of writing feels like a meditation in loneliness and often a study in rejection, so community feels vital. To talk, collaborate, share your work, manifest, dream, and support one another in the struggle helps keep me grounded and focused. The Hmong American Writers’ Circle, CantoMundo, El Taller Latino Americano, and the Laureate Lab Visual Wordist Studio are very specific sources of inspiration in my life. Within these communities, I have encountered others whom I have learned from and created alongside. They have nourished me, and I approach every day trying to put that cariño and energy back into the universe.

Influences: One day Juan Felipe Herrera said to me, “Abandon the left margin.” It was a new liberation to my practice and process. He is also the author of Akrilica (Alcatraz Editions, 1989), a collection that after almost three decades still reaches into the imagination of the possibilities of Latinx poetics. Even to this day, he still gathers others, dreams, and seeks. Witnessing him in action now, and throughout my life, reminds me to stay working toward honoring him as both a mentor and friend in everything I do.

To read a collection from M. NourbeSe Philip is to feel as though I am being invited into the sacred. A space I must read and enter with a care over the next several weeks. Her work re-synapses my understanding of language and navigation of the field in a way that requires me to turn off all other distractions and devote my full attention to her writing.

When I opened The Black Automaton (Fence Books, 2009), my life changed. Douglas Kearney’s ability to have a multiplicity of voices, textures, and histories—all within a visual deconstruction layered in complexity—created something that was new to me. This book made me realize I had to start over and ask more from my writing.

I return to Muriel Rukeyser’s U.S. 1 (Covici Friede, 1938) year after year. More than a primer in docupoetics, her collection delves into the experimental and grounds me with a deeper understanding of how a poem and a collection can be both a reckoning and a path toward truth.

So much of my life involves community that my list could go on and on. Bernardo Palombo, the founder of El Taller Latino Americano, has helped expand my mind. I spent nearly three years in New York City learning about language, art, music, and literature from the entirety of the Americas from Bernardo, an educator, an artist, as well as a songwriter and musician of the Nueva Canción movement. His passion to make space for others; his attention to languages, sounds, and voices; and his ability to scheme and dream against all obstacles astounds me and makes me a better person and poet.

Writer’s block remedy: I walk away. The internet, the algorithm, and capitalism want us to go as hard as we can until we are spent, only to start over again. If I can’t push a project any further, I change mediums or do something else entirely. I write inside a phone book. I break down cardboard and sketch and build. I read and read and read or dive into the internet and research or obsess over a song that I loop and dissolve into for days. Writing is often more about listening than it is about the act of writing, so if the writing ceases, I know it is time I stop what I am attempting, listen more, and reimagine the path.

Advice: Poetry is not a competition or a race. For many years I did not write regularly. I worked. I read. I wandered. For much of my twenties, and even a portion of my thirties, I engaged in a variety of creative projects all while working at nonprofits, as well as at a wastewater reclamation and recycling plant. I did everything except write poems. All those friendships, experiences, and time gave me a chance to slowly understand the book I wanted to write into this world. So feel urgency, but do not confuse that urgency with the need to rush into publishing your first book before it is at a place that you can accept.

The other piece of advice: Find yourself two or three friends, poets or not, you can text a poem to at 3 AM and who will unflinchingly tell you the truth: “Nope” or “This is good, keep grinding” or even “You’ve lost your way.” All the aforementioned replies have helped save me from myself. Without those people in my life, I am unsure what kind of book Borderland Apocrypha would have become, or if it would have even become a reality.

Finding time to write: I have learned that I cannot physically force myself to write, so setting time aside does not necessarily help me write more. Instead, I am often scribbling, sifting through the internet, listening to music, or sitting with an idea, a line, an image, or a concept. As a result, I may not be “writing” while doing a variety of other jobs and things, but I feel I am always mentally drafting and constructing in preparation to write.

Putting the book together: The second and third sections that center the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the subsequent lynchings, hate crimes, and traumas against Mexicans and Mexican Americans in the southwest United States are predominantly in chronological order. The series that begins the collection became the opening section after I realized I was writing a group of poems that created a divergence of pathways, both personal and not, related to my research. Initially I believed I was drafting two separate manuscripts. For the closing of the manuscript, I had at first titled all the poems with the ending clause “as Borderland Apocrypha.” While this maneuver did not make the final manuscript, the dissonance between the title and the subject matter of the poems did help me understand that the poems were steadily drifting from the harms of the past and present, beyond survival, and toward resistance.

What’s next: Immediately after finishing the final draft of Borderland Apocrypha, I returned to the MFA program at Fresno State—I had deferred the last two years of the program. Rather than use the book as my thesis, I made the decision to dive into my paternal grandparents’ experience in the Dust Bowl; make sculptures, both tangible and sonic; create mural-sized poems and scrolls; and assemble a new body of cross-disciplinary work that examines the Dust Bowl, climate change, complicities of whiteness, and annihilation.

I am grateful that this current work is steadily appearing in the world, and the best way I can describe the new work is as an escalation into the borderless aesthetic that I am exploring in Borderland Apocrypha.

Age: 39.

Residence: Fresno, California.

Job: I am currently shifting from my MFA in creative writing at Fresno State to looking for a full-time job. In the meantime I serve on the volunteer communications staff for CantoMundo and as an associate poetry editor for Noemi Press.

Time spent writing the book: Outside of research that began several years ago, the majority of the collection was physically written and revised over thirteen consecutive months. This was an intense period of time during which I simultaneously researched, drafted, drew, constructed, and built poems at all hours of the day and night.

Time spent finding a home for it: It was about a year between when I first thought I was finished with the manuscript but continued tightening the collection to when I heard I had won the Omnidawn Open Poetry Book Prize.

Recommendations for debut poetry collections from this year: Each year poetry gives us a staggering number of debut voices. Some of the collections that left me in awe to share a debut year with include Tommye Blount’s Fantasia for the Man in Blue (Four Way Books), Monica Sok’s A Nail the Evening Hangs On (Copper Canyon Press), Alan Pelaez Lopez’s Intergalactic Travels: poems from a fugitive alien (The Operating System), Benjamin Garcia’s Thrown in the Throat (Milkweed Editions), Michael Torres’s An Incomplete List of Names (Beacon Press), Jihyun Yun’s Some Are Always Hungry (University of Nebraska Press), and Ricardo Maldonado’s The Life Assignment (Four Way Books).