Description

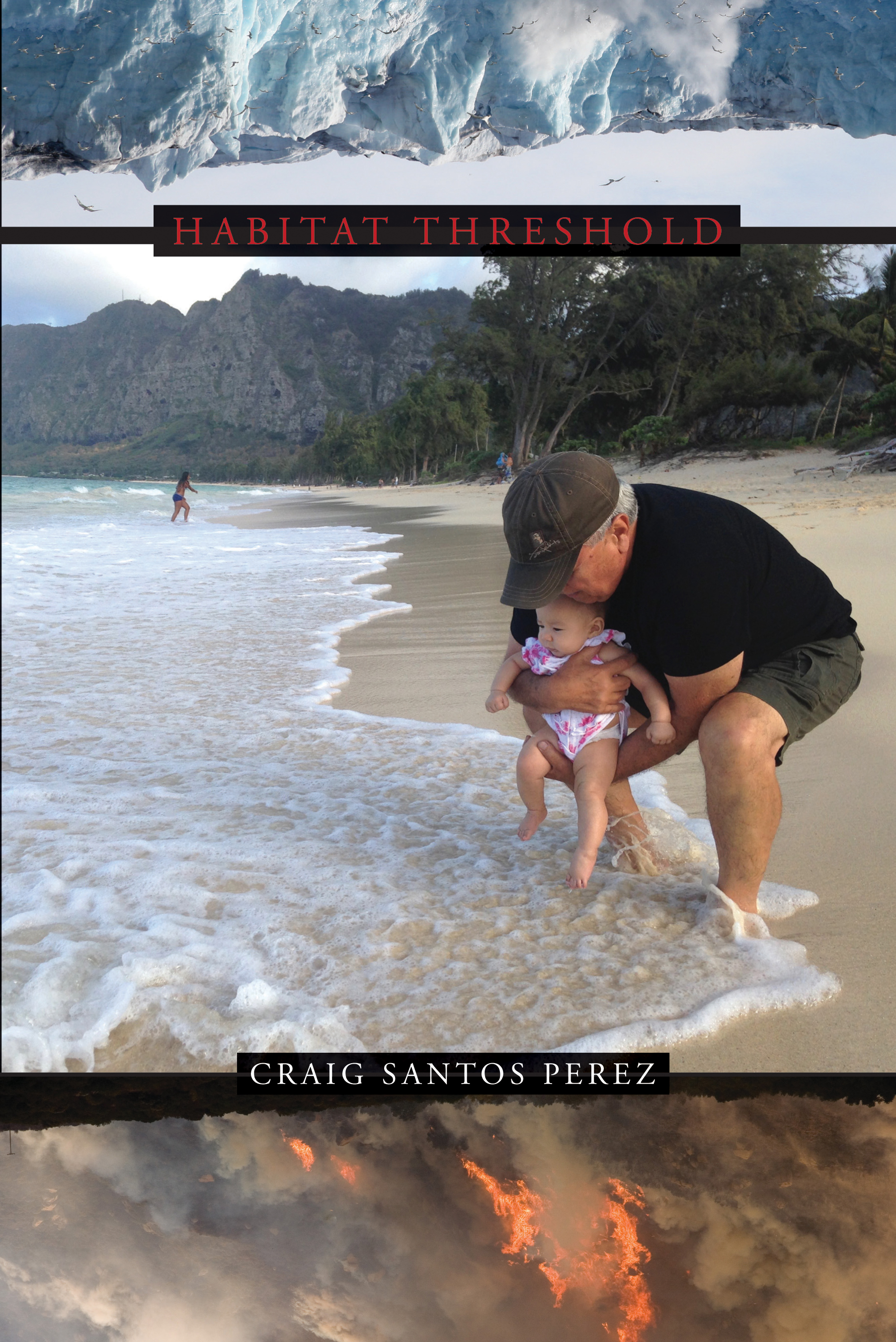

With Habitat Threshold, Craig Santos Perez has crafted a timely collection of eco-poetry that explores his ancestry as a native Pacific Islander, the ecological plight of his homeland, and his fears for the future. The book begins with the birth of the author’s daughter, capturing her growth and childlike awe at the wonders of nature. As it progresses, Perez confronts the impacts of environmental injustice, the ravages of global capitalism, toxic waste, animal extinction, water rights, human violence, mass migration, and climate change. Throughout, he mourns lost habitats and species, and confronts his fears for the future world his daughter will inherit. Amid meditations on calamity, this work does not stop at the threshold of elegy. Instead, the poet envisions a sustainable future in which our ethics are shaped by the indigenous belief that the earth is sacred and all beings are interconnected—a future in which we cultivate love and “carry each other towards the horizon of care.”

Through experimental forms, free verse, prose, haiku, sonnets, satire, and a method he calls “recycling,” Perez has created a diverse collection filled with passion. Habitat Threshold invites us to reflect on the damage done to our world and to look forward, with urgency and imagination, to the possibility of a better future.

Craig Santos Perez returns poetry to its ancient vocation: not only to sing of the dark times, in a public voice, but to sing in and against the darkness. Always exquisite in his attention to the placement of words for power, beauty, and insight, with Habitat Threshold Perez raises poetry to earth magnitude: his pastorals, odes, sonnets, haikus, recyclings, occasional verse, lullabies, and chants sing plainly and with great precision of the vast and intricate inequalities in and through which world-ecology enmeshes us. These are songs of protest, to be recited in places of public debate and decision, and to be learned by children, but also love songs, for family, place, plant and animal, celebrating the many-hued lifeways of humans and their others. The poems find music in inconvenient truths, with a sobering and detailed indictment of our Capitalocene footprint. Habitat Threshold asks us to change our lives: it is motivating, necessary, and inspiring work.

Jonathan Skinner, poet, editor, and founder of Ecopoetics

Essential. Read this book.

Camille Dungy, poet and editor of Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry

Craig Santos Perez is a writer I seriously watch. He includes a variety of environmentally important writing, seamlessly combined with history, politics, and the familial.

Linda Hogan, writer and environmentalist

In this most recent collection, Craig Santos Perez interweaves parental tenderness with knowledge of environmental crisis. With poetic verve and acuity, Perez invites us to the bedside of our ailing world. Formally inventive, these poems read like ritual. The invitation is to come closer, to be with a troubled world. The steady accumulation of these poems will move you to action.

Melissa Tuckey, poet and editor of Ghost Fishing: An Eco-Justice Poetry Anthology

“There’s no half-life of sorrow when our children / inherit this toxic legacy,” Craig Santos Perez writes in Habitat Threshold—and though he is referring specifically to nuclear energy, the line colors everything in the book. No half-life to sorrow: but unending sorrow and rage and terror, expressed in blazing and eloquent poems, at the barely imaginable environmental crisis that has become our world. And still, somehow, tenderness. “I love you without knowing how or when this world / will end,” Santos Perez writes in “Love in a Time of Climate Change,” a poem for his wife, which perhaps speaks also to his little daughter, to the creatures and mountains and sea and air, to us all.

Ann Fisher-Wirth, author and coeditor of The Ecopoetry Anthology

Habitat Threshold is a powerful sequence of poems addressing environmental destruction and how it is associated with racial and cultural hatred and injustice.

Joy Harjo for The New York Times

A native Chamorro from Guam, Perez has challenged colonial dominance in his excellent “from unincorporated territory” series. Here he examines ecological catastrophe in urgent, forthright language, limning a world pushed to the limit by escalating carbon emissions where “Our daughter falls/ asleep in a plastic crib, and I dream/ that she’s composed of plastic,/ so that she, too, will survive/ our wasteful hands.” And he wastes no time in connecting this tragic situation to those marginalized worldwide. Addressing surging tropical storms, “Disaster Haiku” states “the world/ briefly sees us/ only after/ the eye/ of a storm/ sees us,” and Perez highlights the refugee crisis, which comes partly from climate change, by asking, “Will we build/ a tender country, where the only/ documents needed for citizenship/ are dreams of sanctuary?” VERDICT Not just for environmental activists; showing what an informed poetic voice can do.

Barbara Hoffert, Library Journal

With Habitat Threshold, Craig Santos Perez has crafted a timely collection of ecopoetry that explores his ancestry as a native Pacific Islander, the ecological plight of his homeland, and his fears for the future…Throughout, he mourns lost habitats and species, and confronts his fears for the future world his daughter will inherit. Amid meditations on calamity, this work does not stop at the threshold of elegy. Instead, the poet envisions a sustainable future in which our ethics are shaped by the indigenous belief that the earth is sacred and all beings are interconnected—a future in which we cultivate love…

The Rumpus

Sometimes we don’t know whether to laugh or cry with these poems. [Habitat Threshold] invites us to do both to stave off the insanity of our bioengineered Anthropocene. Yet even as climate change and ocean pollution are foreboding presences in these poems, Santos Perez unsettles disaster with familial images of care as a kind of radical desire to reintegrate with the biosphere… This poetry is formally inventive and empathetic… [underscoring] poetry’s power to build and sustain a humane economy of kindness.

Orchid Tierney, Jacket2

[Craig Santos Perez] has been on the vanguard of anticolonial, oceanic poetics… highly invested in the intersections between place and creation. Perez’s most recent collection, Habitat Threshold (Omnidawn), centers sea level rise and the scourge of omnipresent plastics, but also the plights of refugees and citizens, native peoples, fathers and children. Perez plays with form, producing Nerudean sonnets and meandering haiku, as well as a poem in the shape of an antique timepiece, reminding readers in no uncertain terms of the evaporating hours at stake. Its an altogether fitting entry in this prescient poet’s oeuvre, but nonetheless disturbing, aperture-widening, and urgent.

Diego Báez, Kenyon Review

Perez explores environmental themes endemic to his island home and also to the inhabitants of other Pacific communities and the planet as a whole… Perez applies sharp wit and surprising humor through an expansive variety of forms…But it’s perhaps the poems that speak tenderly about his wife and child that will, perhaps, move readers to action.

Michael Ruzicka, The Booklist Reader

Reviews

About the Author

Interview

Craig Santos Perez is an indigenous Chamorro from the Pacific Island of Guam. He is the author of four books of poetry, coeditor of five anthologies, and cofounder of Ala Press. He is an associate professor in the English department at the University of Hawai?i, M?noa. He has received the American Book Award, the PEN Center USA/Poetry Society of America Literary Prize, the Hawai?i Literary Arts Council Award, and fellowships from the Lannan Foundation and the Ford Foundation. In 2010, he was recognized in a resolution by the Guam Legislature as “an accomplished poet who has been a phenomenal ambassador for our island, eloquently conveying through his words, the beauty and love that is the Chamorro culture.”

An interview with Craig Santos Perez

(Conducted for the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center)

We are recognizing the important intersections of war, migration and the environment. What do these intersections mean to you?

As an indigenous Chamoru from the Pacific Island of Guåhan (Guam), the intersections of war, migration, and the environment are very meaningful to me. In the Asia-Pacific region, we have witnessed how hot, cold, and hybrid wars have polluted, contaminated, irradiated, and destroyed our fragile and sacred environments. War and its environmental aftermath has of course led to migrations of peoples whose homes and lands are too often violently sacrificed. In the Pacific, however, we can’t just talk about war, but we also have to address militarism. Many of our islands and the surrounding ocean have been and continue to be exploited as military bases, weapons storage and training, nuclear testing, and live fire and bombing ranges. The “slow violence” of ongoing militarism has also led to migration and environmental injustice.

How have these intersections impacted Guåhan and indigenous Chamoru?

Guåhan has been a U.S. territory (colony) since 1898. The island was actually governed by the U.S. Navy in those years, which began to develop the island into a military base. Moreover, the military government suppressed Chamoru culture and oppressed our people. In the new American schools, for example, kids were punished in school for speaking Chamoru language—a story my grandparents have shared with me.

A traumatic history of Guåhan began on December 8, 1941, when the military of Japan bombed Guåhan—an attack on U.S. forces that paralleled Pearl Harbor. Japan successfully invaded Guåhan, defeated the American military, and occupied the island. Japan also militarized our home island, making it an important base for its imperial ambitions in the Pacific. This occupation lasted for nearly three years, during which many atrocities against Chamorus occurred, including forced labor, rape, torture, land dispossession, and massacres. The U.S. military invaded Guåhan in 1944 and eventually defeated the Japanese forces and reclaimed the island. Both of these invasions, as well as the battle between two empires, devastated the environment and people’s homes. While my grandparents survived the war, they never forgot their traumatic experiences during this violent time.

After the war, the U.S. military continued its efforts to turn Guåhan into “an unsinkable aircraft carrier,” or what some have referred to as “USS Guam.” The military displaced many Chamorus from our ancestral lands to make way for military bases, munitions and fuel storage facilities, military housing, and live firing ranges. Today, thirty percent of the landmass on Guåhan is occupied by the military. This ongoing militarization has led to profound environmental damage to our lands and waters. Studies have found more than a dozen contaminated and toxic sites on Guåhan (including “Superfund” sites) due to military dumpsites and the leaching of chemicals. The air force base in northern Guåhan has been found to have leached “forever chemicals” into the main aquifer. Moreover, the entire island was exposed to radiation because Guåhan is located “downwind” from the nuclear testing that occurred in the Marshall Islands. During the war in Vietnam, Agent Orange were stored in drums on Guåhan and leached in the soil. This history of environmental contamination due to militarism has resulted in high rates of cancer on Guåhan and Chamorus suffer from significantly higher rates of cancer than other ethnic groups.

Militarism and environmental injustice intersects with Chamoru migration in several ways. First, it is important to note that Chamorus became U.S. citizens in 1950 as a result of the Organic Act of Guam. In the subsequent decades, Chamorus would be drafted or voluntarily enlist in the armed forces. Chamoru soldiers, along with their families, would be stationed at bases throughout the states. For example, Chamorus ended up in cities near military bases, such as San Diego, CA; Tacoma, WA, and Corpus Christi, TX. Today, Chamorus have extremely high enlistment rates, and military service is still the number one reason why Chamorus migrate. The other reasons why Chamorus migrate include economic and educational opportunities and health care. Sadly, these are sometimes related to the environment and militarism. Many Chamorus who migrate to receive better healthcare often suffer from cancer. Other Chamorus who migrate for work are often landless Chamorus and struggle to survive in Guåhan due to the high cost of living on island. Unfortunately, so many Chamorus have migrated over the last fifty years that those of us off-island now outnumber our on-island kin. There are even generations of Chamorus who have been born in the states and have never even been to Guåhan. According to the 2010 census, Chamorus are the most “geographically dispersed” Pacific Islander population in the U.S. The largest Chamoru diasporic population lives in California (44,000), with Washington (14,000) and Texas (10,000). I live in Hawaiʻi along with 6,600 other Chamorus.

What would you want K12 teachers to know about these impacts, and why?

I would want educators to know the basics of Guåhan’s history and how it has been colonized by the United States. I would also want them to know how militarism has impacted our lands and waters, and how it has led to a vast Chamoru diaspora. This is important to know because Chamorus and other Pacific Islanders are one of the fastest growing migrant populations with the U.S., yet very little is known about our histories, cultures, and reasons for migration. I believe that cultural understanding can lead to deeper empathy for Pacific Islanders. I think this knowledge is also important for K12 teachers because they may have Chamorus and other Pacific Islanders in their classrooms, and it would be transformative and empowering for our peoples to see ourselves in the curriculum.