Description

The poems begin where language fails, where speech becomes disembodied, and syntax skids to a stop that dissolves into gesture. Where its form reaches an end, formlessness offers a space ripe with possibility. Here we find Harpo, reaching into the frustrated endpoint of language to find a method for its resurrection. Fry sees that language becomes a tool for alienation and uses the poems in Harpo Before the Opus to excavate paths back to tenderness. These are poems from the edge, pulling language out from its failure and into a fervent interrogation of its possibilities. What was once a tool of capitalistic alienation now serves as material for building connections.

In spiraling explorations of rhetoric, these poems allow language to break from its prescribed structures, and instead, it becomes a gestural embrace of feeling and being. Fry utilizes a Marxist lens to scrutinize and reinvent the use of language. In Fry’s hands, language is rendered a visceral and sensual material, forming poems that are both deeply felt philosophical inquiries and wildly playful exercises of wit.

What is a shape / Except resistance,’ Fry asks himself, and the poems of Harpo Before the Opus—in all their prosodic diversity, technical and historical lexicons, and affective topographies—may be read as the literary manifesto for a resistance movement of one. Yet Fry also shows us how resistance may be grounded, all too often, in unacknowledged complicities. . . Such plentitude of being holds open the possibility of companionship, and perhaps even comradeship.

Srikanth Reddy, author of Voyager

Here is rare beauty, a delirium of language feverish, passionate; an abstract pitched and wounded critique. Mute Harpo talked music but here speaks in word ravishments that send me to the dictionary to reconsider the obvious, reconsider the ordinary — like Cow, Red, Berm, Fondant. . .I Give, I Took. Harpo stammers compulsively in Justice, for Justice, as here they might meet up in Kant’s Kingdom of Ends: Being nests its midst in me. Here is a solid iron made malleable and the deep terrors of groundlessness…an intellectual verbal allegory of air with Venus poised shaky on the half shell. Vertigo professes through a glass darkly that at first hinges on underlying/outlying shames but then rises to meet the eye and clear the palate of the senses – with keen attention. And though NOT ENOUGH stands on the back of EVEN LESS in shrouds of awful bleakness, attempts at smugness repeatedly fail. And Reality puzzles. And Will puzzles. What is accuracy, where is truth? Harpo stands before the opus and says flat out:I allege a norm compels

Karen Garthe, author of the hauntRoad

Born and raised in rural Ohio, Logan Fry resides in Austin, Texas with his wife, Caroline, and their three boys, Wolfie, Hank Scorpio, and Barthelme. He received his MFA at the University of Texas and now teaches writing at Texas State University. Fry is the founding editor of Flag + Void, and his poetry has appeared in New American Writing, Fence, West Branch, Boston Review, Prelude, Denver Quarterly, and the Best American Experimental Writing anthology.

^ back to menu

A brief interview with Logan Fry

(conducted by Gillian Olivia Blythe Hamel)

I was excited to see Srikanth Reddy select Harpo Before the Opus as winner of the 1st/2nd Poetry Book Prize – our panel of editors had pulled it forward as something that stood apart from many of the other manuscripts we were considering, a singular experiment in the speech act. In your own description of the work, you talk about mirrors, about self-exile, about language and speech becoming its own embodiment. I wonder if you could elaborate on this in regards to your composition of this book – how did the subject coalesce, and where did your craft as the writer end and the poems’ embodiment begin?

The book really found its crux when I abandoned a years-long mode of writing poems purposefully devoid of a central speaker. It felt important, pressing, at the time, to write poems without a figure there to inhabit the thinking and the feeling of the poem. It was a limiting stage by design, an engine intended to burn away.

Where that detached mode took me was to a more nuanced conception of voice within the poetic register. It revealed embodiment as a purer route to language as an enactment of idea and image, one that allowed for a wider range of language and accommodated speech acts more capaciously by folding them into a decentralized “I.” So embodiment was the literal process, then—one routed thru disembodiment as a control group to relocate a self within the poems.

Figuring out how, and what, I wanted to embody was found in the structure of Giorgio Agamben’s “whatever singularity,” a concept in which “singularity is thus freed from the false dilemma that obliges knowledge to choose between the ineffability of the individual and the intelligibility of the universal” (The Coming Community, p. 1). Later on, Ben Lerner’s The Hatred of Poetry mapped poetry over this concept by means of its virtual/actual divide. He saw the divide as irresolvable, and thus as what accounted for the widespread cultural exalting and simultaneous derision of poetry.

But if it’s instead the poetry that’s irreducible, the divide’s resolved. The universal is the quark of the virtual. The individual is the quark of the actual. The thin penumbra where they meet is where I want these poems to live.

One way you’ve talked about these poems is that they ‘aim to instrumentalize the common good of language into gesture set against the gestalt of capital.’ There is a preoccupation here with language that wears an aura of the public: a magnifying glass held to abstraction, crumbling monolithic nouns. Can you talk about this book’s approach to language’s life in the sociopolitical sphere, to embodying a discourse that is both ineffably communal and somewhat at the mercy of our ability to agree upon it?

Before I realized the muteness of Harpo Marx was the prevailing gesture-matrix of these poems, I thought that it was Caliban’s enraged retort. “You taught me language; and my profit on’t / Is, I know how to curse. The red plague rid you / For learning me your language!” (The Tempest I.ii.363-5).

The fact that language is a product of several passes through abstraction’s threshers is good to remember. I wish more would keep this in mind, in a daily sense. But where the stakes are higher in formal Politics, it’s especially crucial to recognize how language is the gate the privileged have made for a more formalized excluding from foundational rights. They demand the presentation of an exact arcane incantation as the spell that will, allegedly, unlock the gate while pretending it’s a mere and simple logic they request and which guides their callous disregard.

And yet—it’s not the language that’s vile. As a mediator of thought, language betrays what’s rotten better than what’s good or pure. The deep irony of Caliban is that the ability to curse his master is an inevitably more limiting enslavement. To those already gifted with the curse of language, becoming more adept at naming the systems that hamstring our fulfillment is empowering. But, for Caliban, the power is coterminous with the enslavement, not a way to recognize and process the binding chains but instead a naming that made them material.

The last poem in the book, “Too Benign Is Candor,” contains the line “The equilibrizing tank / Loves flux,” and when I reflect on Harpo Before the Opus at this stage, this seems apt for how the book processes these themes. We love what offers purpose. The alienation late capitalism inculcates in its subjects brings about an ambient anxiety that draws us toward small self-degradations because we intuit what a purposeless lie it enforces. The tank’s sole purpose is to keep the water level. It’s happy because the water’s purpose is to slosh.

That’s why Harpo is the model of optimism I want to embody a stark face-to-face reckoning with the darkness of our time in the (let us hope) late stages of capitalism. It’s not that Harpo can’t conceive of speech. Each gesture is instead an active, emotive rejection of the curse.

The intimacy of these poems is striking to me, partly because it exists in contradistinction to this experiment of language-on-its-own-terms and partly because such an experiment would inevitably result in intimacy: without the veil of intention, speech itself would be the ultimate gesture for any and all audiences to coinhabit. When you speak of the post-performative, how do you envision the work’s relationship to the reader in this sphere? What kind of intimacy germinates when performance falls away?

I take seriously the principle that a poem is what can’t be paraphrased. That what makes a poem a poem is what in it evades summary. That’s why, when I consider my poetics post-performative, it’s as an approach to language that overflows signification, that spills into enactment in the way of the traditional examples of performative utterances. Any word can be imbued with the aura of oath.

I want the reader to experience the post-performative poem as an emission from Gabriel’s horn, its finite volume enclosed in infinite surface area. If there is only so much to be expressed, only so many narratives, the expression itself must take on a plumbless depth of surface. The intimacy of a poetry like this is that gesture requires grappling with the tangible that remains tangible. There an underlying trauma in being accustomed to the world’s entropic tendency, but a poem can subvert this. There’s no reason a poem needs to erode.

The intimacy a post-performative poetry offers comes via its endurance. There’s a promise that what is contained will be held in the space participation creates. This participation is a way to make poetic language’s gestures irresolvable—a thing that doesn’t diminish by its expression but instead reifies its form. That’s why, as a reader, I feel cheated by writing that gains its density by encoding. Sure, decoding’s fun, but once the safe’s cracked, you’re left with just a bare box, its door left ajar.

I want the raccoon to get to enjoy her marshmallow and to dunk it in the puddle.

I want these poems to be cakes the reader eats and still has too.

I’d love for you to talk about any writers, artists, thinkers who have influenced you in this work; in what direct or indirect ways have you felt this influence? And perhaps you could talk about who you’re reading currently? With whom do you feel a kinship, a provocation, a catalyzing relationship of some kind?

The catalyzing kinship that I feel is narrow in range but not in depth. It’s a unit of two—my co-editors at Flag + Void, Caroline Gormley and Matthew Moore. It’s no coincidence that this is the case, nor that each has such a prominent place in my personal life (to the extent that I married one of them). Getting to share in their abundant generosity of spirit, their wild humor and rigorous intellect, and to write and edit and exchange poems with them has been exceptional luck for my art and my life.

The wider influences on my work start with them, too. Agamben’s aforementioned The Coming Community, a gift from Matt, gifted me the vocabulary for the invisible structure he could see I was under the hood of with my poems. And I wouldn’t have had, at a crucial point I did, Chelsey Minnis’s Poemland—the book I’ve read more times than any other, by a wide margin—if Caroline hadn’t put it in my hand.

In Wayne Koestenbaum’s phenomenal The Anatomy of Harpo Marx I found this book’s embodiment and a probing, obsessive, dissection of what speechlessness diffuses into gesture’s endless uninterpretation. The work of Sianne Ngai on aesthetics and Lauren Berlant on affect and desire and Cal Bedient in and on poems and with Lana Turner, too, and perhaps that’s where I’d tide the flood of poets that would come except to limit it to the slabs of a path from Stevens to Berryman to Ashbery to Barthelme to Notley to Donnelly to Reines.

I need to note R.D. Laing’s Knots as a guidebook to gesture and communication that I mined for Harpo, but one so potently, viscerally accurate that I can’t read it. More than a page and I have to throw it down to stretch my seized-up limbs and briskly, aimlessly walk. A recent book that accomplishes the opposite of this—an intellectual anticoagulant and balm—is lazenby’s Infinity to Dine.

If I need something to look at, I’m looking at Cy Twombly first.

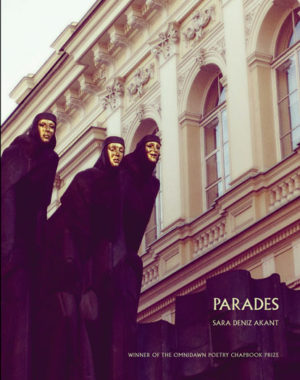

You were instrumental in the selection of the image that is used in the cover design for this book. Would you describe your considerations regarding the cover image? How does this image align with your intentions for the book?

Matthew Palladino’s art came to my notice some years back via Instagram’s suggestion algorithms, and I mention that particular mundane detail because the spirit of play with commodification permeates his work. The reliefs are what stand out most on this theme: the repurposing of readymade (and, now, self-fabricated) candy molds to shape bright, patterned, highly textural paintings that look like they could have emerged from an assembly line where the bumbling workers spilled their respective pulp comics and AbEx textbooks into the plastic mold.

I hadn’t seen Troy’s Lament, the cover image, until this book became real and I was searching purposefully for its face. So the confirmatory jolt that struck me when I clicked thru to it in the gallery was a feeling I knew I could trust. Harpo Before the Opus was conceived within and via a period of interpersonal change and growth and confusion and investigation for me. I was trying to conceive of how we relate to one another, how little “communication,” the useless term, does for its crucial task. Troy’s Lament captures the plainness and unsolvable task of human connection. Its figures are in profile, affixed flatly in blue sky between mechanically-perfect cliché imitations of clouds above (of course) and …well, it’s not clear what’s below. Or what’s between them, which seems the same as what’s below, or where their hands begin and end, or their feet, or legs. They two figures are locked into symmetry and resolutely but undefinably linked by the same muted, squiggly, bulbous matter from which they emerge, the fundament on which they rest, which distinguishes them as distinct figures. At least until you notice their fundament-swirls are not merely mirrored, but the same, read left to right. The subconscious-pleasing simplicity gives way when the eye lingers and adjusts—like staring into the depths of a pool only to realize your eyes have been affixed to something bobbing on its surface all along.

I realize that I’ve spent a lot of time just stating what can easily be seen if one is to look at the image. That—mere looking—was the extent of my initial consideration, because Palladino’s art is exceptional in how it provides its depth via an immediacy that persists. I would hope that my poetry offers the same.

^ back to menu