Description

Winner of the 2011 Omnidawn Open Poetry Prize

Selected by Carl Phillips

The word loom calls us to the edges, perhaps even limits, of life—to what appears as the space and means of creation—and to what appears on that horizon, soliciting reflection and response. In Sarah Gridley’s third collection of poems, the word serves as emblem and omen, as signal object of meditation. At the loom—and looming—is The Lady of Shalott—poetic specter of Tennyson’s surfaced—and silenced—anima. Trusting in the deep ambiguities of text and textile, spirit and matter, masculine and feminine, Loom calls the Lady back to life, out of isolation, circumscription, and distraction. A book of poems set against the work of disconnection, Loom searches for reconstructions of gender, dwelling, and the sacred.

“Not inside us or outside us, but the obbligato pressing on between.” One of Loom’s concerns is the tension between inside and outside, between the outside world that contains and in part defines us, and the interior of self that we know best in the “slow darks/of elected solitude.” It makes sense, then, that an underlying theme – or obbligato – of Loom is Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott,” a equally mysterious text that, among other things, includes a woman weaving at a loom, whose only vision of the outside world is in a mirror until, fatally, she turns toward the actual world, and the mirror cracks. Loom seems at times a Book of Hours both contemporary and medieval, illuminated everywhere with intellect, grace, and a persuasive belief in beauty; at other times, something woven of many histories – private, natural, literary – a fabric that at once conceals and discloses. This indefinitiveness is part of the point here: “Let nothing speak to/or touch/what the story truly feels.”

Carl Phillips, judge of the 2011 Omnidawn Open Poetry Prize

Loom is a glass & a gloss, a pastoral meditation & a postmodern allegory, a profound retelling of a Victorian ballad’s rendering of a medieval tale. Interweaving text, texture, a shimmering shadow world of appearances, Gridley’s luminous intellect, translucent language – “rouging silver and wildly cold” – brings us again & again to our senses, to what abides. No poet writing today has as chaste a tongue, as pure & austere an ear as Sarah Gridley. In the tradition of her feminist masters Dickinson & H.D., she returns us to the morning of the world, that first bite of the apple of language.

L. S. Asekoff, Author of Freedom Hill

Sarah Gridley’s swish new collection, Loom, is a fine weft and warp of visceral beauty embodied by its occasion. From a “dragon-handled letter opener” to unsliced book-bound pages, the world in these poems and the speaker who speaks them stand in complex defiance of the adage that “only something useless can be beautiful.” Wearing Auden’s “poetry makes nothing happen” while relishing a fetching paperlessness, the useful uselessness of this work is enacted exquisitely in ways both “difficult to remember,” and “hard to explain.”

Sandra Doller, author of Man Years

About the Author

Reviews

Excerpt

Sarah Gridley is the author of two previous books of poetry: Weather Eye Open and Green is the Orator, both from the University of California Press. Born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1968, she received a BA in English, magna cum laude, from Harvard University in 1990. She wrote her senior honors thesis on Dylan Thomas, a poet introduced to her by her father, who grew up outside of Cardiff, Wales. At Harvard, Professors Marjorie Garber and Helen Vendler reinforced her love for poetry and her interest in teaching. After a year working on a vegetable produce farm in Sagaponack, NY, and living and working in Greece, Gridley completed an MAT in English at Tufts University in conjunction with the Shady Hill School Teacher Training Course in Cambridge, MA. She went on to teach high school English at the Hopkins School in New Haven, CT. She then moved to Boston, MA, where she worked as Director of Program and Publicity for The Ford Hall Forum, a public lecture series dedicated to upholding First Amendment rights and encouraging civil debate. in 1998, Gridley pursued an MFA in poetry from the University of Montana, where she studied with poets Patricia Goedicke, Joanna Klink, and Greg Pape. After receiving her degree in 2000, Gridley moved to midcoast Maine, where she lived and worked for six years. In the fall of 2006, she returned to her native city of Cleveland for a visiting lecturer position in the English department at Case Western Reserve University. She is now an assistant professor at Case. In 2009, she received a $20,000 Creative Workforce Fellowship from Cleveland-based CPAC: Community Partnership for Arts and Culture. Using the fellowship money to take a partially compensated leave from her teaching duties in the fall of 2010, Gridley returned to Maine for a writing retreat, where she began work on what would eventually be the poetry manuscript, Loom. In the summer of 2011, pursuing a growing fascination with Tennyson and Julia Margaret Cameron, she visited Farringford and Dimbola, their respective neighboring homes on the Isle of Wight, UK.

A brief interview with Sarah Gridley

(conducted by Rusty Morrison)

How/why did you begin Loom? What initiated the work?

An act of memorization initiated the work of Loom. The summer of 2006, before leaving Maine to move to Cleveland for my current work at Case Western Reserve University, I decided to memorize Tennyson’s poem “The Lady of Shalott”—a poem that had haunted me for years. I did the memorization in tandem with a daily walk at a place called “Morse Mountain” in Phippsburg. The walk was about a mile in length, beginning in the woods, and opening to the Atlantic. The final 1842 version of the poem is 171 lines in length. The majority of the lines have four beats, with the exception of the refrains, which have three. This is a good walking poem. And not a difficult poem to memorize, thanks to its entrancing rhyme scheme and vivid imagery. I had thought to dispense with the haunting sensation this poem gives me by memorizing it, but if anything, committing it memory only complicated the obsession. George Steiner says of memorization: “What we know by heart becomes an agency in our consciousness, a “pace-maker in the growth and vital complication of our identity.” This was certainly the case with this poem. Through this process of knowing it by heart, I discovered it was acting on me in ways I still did not understand. Its “agency” in my consciousness was much stronger—and stranger—than I’d thought.

Tennyson today is considered by many a fusty, programmatic poet, who, as Laureate appointed by Victoria, participated in the kind of priggishness we now find so suspect about the period. As Walter Houghton wrote in The Victorian Frame of Mind, “Of all the Victorian attitudes the hardest for us to take is dogmatism. The imperious pronouncement of debatable doctrines with little or no argument, the bland statement of possibilities as certainties and theories as facts, the assertion of opinion in positive and often arrogant tones—in a word, the voice of the Victorian prophet laying down the law—this sets our teeth on edge.” Houghton was writing this from an early 1960s vantage point. From today’s postmodern perspective, the so-called “pre-eminent poet” of the Victorian age might seem even less sufferable/creditable. As one of my friends said recently, Tennyson is possibly one of the most “condescended to” poets of all time.

But I see and hear a different Tennyson beneath the very public persona—the celebrity status—he assumed. I read him as a deeply conflicted and complex poet, caught between what I call the gloom and the gleam. A suppressed mystic. A melodious but often deeply weird “ear.” And, despite the seemingly disparate contexts of the Victorian and postmodern periods, there are correspondences between them that fascinate me: anxieties about new technologies; strains between scientific advances and religious and ethical responses to them; political reforms and upheavals; cross-sweeping currents of “popular” culture (to wit: Victorian mania for postcards and contemporary mania for Twitter, Facebook, etc.). At first I felt embarrassed about my growing obsession with Tennsyon—even apologetic about it—but then I realized how important it was for me to follow that obsession as faithfully as I could. I have for years been teaching the Richard Hugo directive of following your obsession, but it wasn’t until this book, Loom, that I really gave it free reign in my own work. In reading biographies and critical works on Tennyson, and in performing close readings of “The Lady of Shalott,” I was led down wonderful paths: early photography; mirrors; swans; weaving; feminist theology; eco-poetics; Arthurian legend, etc. The poems in Loom are the processing or metabolizing of many hours of Tennyson puzzling.

How did you come to choose the title of this book?

I knew I wanted a one-word title, for starters. My previous two books were “strips” of quotation—the first, Weather Eye Open, is borrowed from a nautical saying. The second, Green is the Orator, is borrowed from Wallace Stevens’ poem, “Repetitions of a Young Captain.” I wanted a one-syllable word that would both concentrate a reader’s attention, and still oscillate, or vibrate, within that moment of concentration. I liked Loom for its double “o” eyeballs, reminiscent of the scoping the Lady of Shalott does from her tower, and of course I liked the switchbox it creates as it shifts from a noun to a verb sense. The noun form, the site of weaving, conjures figures like Arachne, Penelope, Spider Woman of the Native American tradition, and the Lady of Shalott. The verb form conjures the edges of creation, what looms on the horizon in both hopeful and menacing ways. In ancient Greece, the component directions of a loom, warp and weft, were gendered masculine and feminine, respectively. Thus Loom as a title required a reckoning with gender distinctions and intersections, with what I experience as the divine male and the divine female. The words text, textile, tissue, and texture all derive from the Latin verb texere, to weave. I wanted to sit, as it were, inside that apparatus, that loom, to see what such associations were capable of producing, or rather, connecting.

What, specifically, were some of the most interesting surprises you encountered or most daunting challenges you faced as you worked through the writing of the poems in this book? Did the writing of this book change you in any ways?

In his judge’s citation, Carl Phillips says something very helpful to me: he says that Loom feels like something “woven of many histories—private, natural, literary—a fabric that at once conceals and discloses.” He goes on to say “This indefinitiveness is part of the point here: ‘Let nothing speak to/or touch/what the story truly feels.’” One of the most daunting challenges for me in writing Loom was trusting the difference between “indefinitiveness” and incomprehensibility. Rusty Morrison helped stay my impulse, during the editing process, to gloss the poems. I came to a surprising recognition that this project need not exhaust or explain my fascination with Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott”—that I can let the poem preside inside Loom not as a solved puzzle, but rather, as a rich and engaging mystery. Also I would say writing this book drew me deeper into theological and ecological concerns—and their potential crossing places in feminist poetics.

Who are the authors with whom you feel a kinship with now? &/or Who are you reading currently?

I don’t want to presume kinship with these poets, but these are the poets whose work is most helpful and compelling to me now: Jay Wright, Robert Duncan, H.D., Dylan Thomas, Joy Harjo, Brigit Peegan Kelly, Seamus Heaney, Anne Carson, Susan Stewart, Alice Oswald, Inger Christensen, Odysseus Elytis, A.R. Ammons, Wallace Stevens, Gerard Manley Hopkins. There’s so much to read! Outside of poetry, I read feminist theologians such as Catherine Keller and Grace Jantzen. I am interested in Elizabeth Grosz’s thinking about time, and Yi Fu Tuan’s work in cultural geography. Other writers who interest me: W.G. Sebald, David Malouf, John Berger, Julie Otsuka, Sara Maitland, Tacita Dean, Marina Warner, Alphonso Lingis.

Would you tell me about yourself, your history, your interests?

Regarding my history, or some of the discernible features of it: I was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1968. When I was ten, my family moved to Tokyo for six months. This time in Japan stamped my soul. My memories of Japan, 1978, are marvelous to me. I think they continue to feed my imagination. I very much hope to go back again one day. I received a BA in English, magna cum laude, from Harvard University in 1990. I wrote her senior honors thesis on Dylan Thomas, a poet introduced to me by my father, who grew up outside of Cardiff, Wales. At Harvard, Professors Marjorie Garber and Helen Vendler reinforced my love for poetry and interest in teaching. After a year working on a vegetable produce farm in Sagaponack, NY, and living and working in Greece, I completed an MAT in English at Tufts University in conjunction with the Shady Hill School Teacher Training Course in Cambridge, MA. I went on to teach high school English at the Hopkins School in New Haven, CT. Then I moved to Boston, MA, where I worked as Director of Program and Publicity for The Ford Hall Forum, a public lecture series dedicated to upholding First Amendment rights and encouraging civil debate. In 1998, I pursued an MFA in poetry from the University of Montana, where I studied with poets Patricia Goedicke, Joanna Klink, and Greg Pape. After receiving my degree in 2000, I moved to midcoast Maine, where I lived and worked for six years. In the fall of 2006, I returned to my native city of Cleveland for a visiting lecturer position in the English department at Case Western Reserve University. I’m now an assistant professor at Case. In 2009, I received a $20,000 Creative Workforce Fellowship from Cleveland-based CPAC: Community Partnership for Arts and Culture. Using the fellowship money to take a partially-compensated leave from teaching duties in the fall of 2010, I returned to Maine for a writing retreat, where I began work on what would eventually be the poetry manuscript, Loom. In the summer of 2011, pursuing a growing fascination with Tennyson and Julia Margaret Cameron, I visited Farringford and Dimbola, their respective neighboring homes on the Isle of Wight, UK.

Regarding my interests: I would say the top two are gardening, and having good friendships.

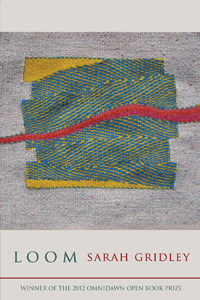

You selected the artist and artwork that is the primary image for the cover design for this book. Can you speak to this wonderful piece of art and its relationship this text?

The artwork that graces—and I really mean graces—in the sense of conferring honor to the whole project with its particular presence—is a piece of weaving by textile artist Alex Friedman. It is called Rift Flow. Originally I had thought about seeking permission to use William Holman Hunt’s painting of The Lady of Shalott as a cover image, but I came to think it would have been too delimiting, with respect to the title as well as the collection as a whole. While the Lady of Shalott is certainly a guiding spirit, as it were, for the collection, the poems work off and through wider associations, too. Also, as a side note, Tennyson expressed serious displeasure with his friend’s rendering of the Lady. He criticized in particular Holman Hunt’s depiction of her hair, which he said, looked “wildly tossed about as if by a tornado.” I happen to love her hurricane hair, and in fact have a framed poster of this painting hanging above my desk. But as I said, I realized I wanted an image that would open itself to wider associations. At the same time I realized I wanted an image of an actual weaving, not a representation of someone weaving. I wanted the warp and the weft to be discernible, to call to someone’s tactile imagination. I knew I wanted the weaving to be made by a woman. I searched through The American Tapestry Alliance and found Alex Friedman’s work there. I then went to her website and immediately fell in love with the piece she calls Rift Flow. This is part of a series she calls “small tapestries.” It is only 11 x 11” in size, and that miniature nature appealed to me. I read somewhere that a piece of weaving is sometimes referred to as a “web” (Tennyson: Out flew the web and floated wide…), and I liked to imagine Rift Flow as being roughly the horizontal/vertical span of an actual spider web. In addition to the appeal of its size, I was greatly attracted to the way the image hovers between abstraction and representation. I see a blue river banked by golden grain (Tennyson: On either side the river lie/Long fields of barley and of rye), but I also see a potent “red thread” life- force running through it. A rift is a crack, split, or break in something. The red is both a rift and a kind of vital suture. I am reminded of a favorite quote from Maurice Merleau-Ponty: “We may think of the sensing body as a kind of open circuit that completes itself only in things, and in the world. The differentiation of my senses, as well as their spontaneous convergence in the world at large, ensures that I am a being destined for relationship: it is primarily through my engagement with what is not me that I effect the integration of my senses, and thereby my experience of my own unity and coherence.” Rift Flow makes this idea of inherence immediately and passionately real to me. It is startling and comforting at the same time. Thank you Alex!

Before and after the prose, Gridley places short units of spell-like verse, featuring forests and mirrors, tidal spaces “like the slang for living sea urchins” and white space where “the imaginary world seems promised here.” The Lady’s, or Gridley’s, lines can at times feel labored or showy, but can also invite us in-: “The woods feel best/ when barely raining, when talking scarcely resumes// in the greater space/ of holding still.”

Turning on unexpected facts so that they frequently surprise and delight the reader, the poems here are full of intelligence and wonder that connect the reader to the natural world.

Gridley’s is a fully breathing poetry that is intimately involved with its allusion. It is quiet and voluminous. It is settled and concise. If you were to consider the Arthurian folktale-ish element of “The Lady of Shallot,” Loom immerses itself in the mystery of the folk. It almost feels lost in this immersion. But because of the tragic figure of Tennyson’s poem, Loom remains poignant and immediate.

The poet of Loom is a poet of meditation and her far longer text is infused with her source and likewise musical, imagistic, and frequently mysterious. Sarah Gridley creates an immersive world of echoing correspondences and mirrored reflections: intertwined poems (The Lady/Loom), of book and web, of lines of poetry with lines of thread, of the doubling of women and the doubling of mirrors, of the living and the dead, of the inside and outside, of a medieval pastoral and the landscape of Ohio or the Isle of Wight.

Loom has a magnificent sense of rhythm, one that resonates throughout. Using the Tennyson poem as a stepping-off point, the poems seek out weave and unfurl, carefully working to explore the smallest moments around and between such a well-known Victorian ballad. As she writes in the first section: “What range of tones are possible / in the phrase See for yourself? // It is hard to explain. / Bloom is a noun and bloom is a verb.” Despite the occasional urgency, there is a meditative stillness that emerges through Gridley’s lines, quietly demanding an increased attention. Even more than usual, the reader is forced to listen.

Loom is more than just a necessary updating of “The Lady of Shalott”; it improves on the narrow perspective of the isolated female artist by transforming Gridley’s ideas and interests into a lyricism that deeply enhances our understanding of the complexities of both the Victorian era, and our own contemporary moment.

Gridley’s Loom begins with that tension between reflection and experience. She writes, “Thoreau said the perception of beauty // is a moral test—and—How vain it is / to sit down and write // when you have not stood up to live.” Gridley does not separate the mediated “world of shadows” (perhaps the province of writing, reading, perception) from the factual world we experience through all the senses; at times one serves as the warp, the other the weft. They are fused, and at times productively confused. The word “loom” itself denotes both the perceived phenomenon—to loom, to suddenly appear into view, to appear distorted—and the apparatus for making garments. Gridley’s keen attention to the etymological histories of words invites us to do the same. Within the rich “textile” we read the “text.” One senses that for Gridley the act of reading is a lexical experience, a transportive event.

Loom has a magnificent sense of rhythm, one that resonates throughout. Using the Tennyson poem as a stepping-off point, the poems seek out weave and unfurl, carefully working to explore the smallest moments around and between such a well-known Victorian ballad. As she writes in the first section: “What range of tones are possible / in the phrase See for yourself? // It is hard to explain. / Bloom is a noun and bloom is a verb.” Despite the occasional urgency, there is a meditative stillness that emerges through Gridley’s lines, quietly demanding an increased attention. Even more than usual, the reader is forced to listen.

Loom is more than just a necessary updating of “The Lady of Shalott”; it improves on the narrow perspective of the isolated female artist by transforming Gridley’s ideas and interests into a lyricism that deeply enhances our understanding of the complexities of both the Victorian era, and our own contemporary moment.

Gridley’s Loom begins with that tension between reflection and experience. She writes, “Thoreau said the perception of beauty // is a moral test—and—How vain it is / to sit down and write // when you have not stood up to live.” Gridley does not separate the mediated “world of shadows” (perhaps the province of writing, reading, perception) from the factual world we experience through all the senses; at times one serves as the warp, the other the weft. They are fused, and at times productively confused. The word “loom” itself denotes both the perceived phenomenon—to loom, to suddenly appear into view, to appear distorted—and the apparatus for making garments. Gridley’s keen attention to the etymological histories of words invites us to do the same. Within the rich “textile” we read the “text.” One senses that for Gridley the act of reading is a lexical experience, a transportive event.