Description

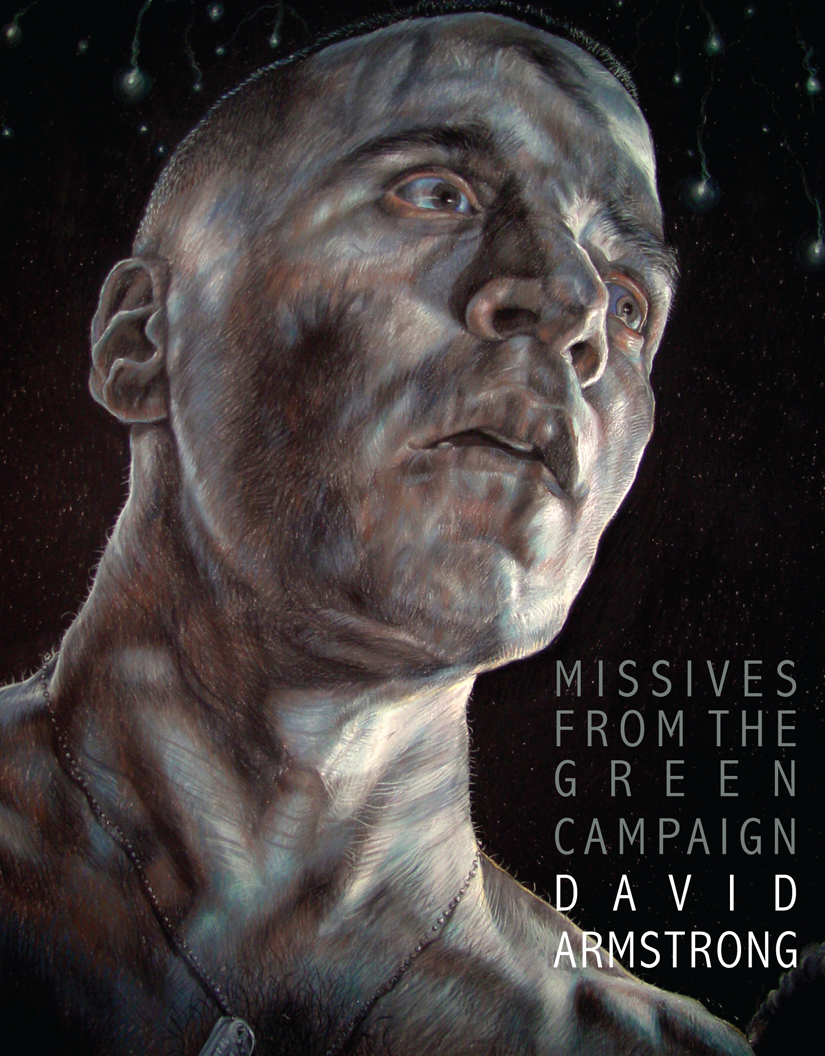

Winner of the 2015 Omnidawn Fabulist Fiction Prize

Selected by Brian Evenson

In a future short on fossil fuels and flora, the military compels its soldiers to carry houseplants wherever they go. To allow a plant to die is treason. Hershel Boyd is by all accounts a poor soldier, a frail, overeducated believer in the fading freedoms of a dying country. The narrator, a fellow recruit, makes it his mission to protect Hershel against all dangers. From the hazings of basic training to a botched invasion of the rainforests of South America, the two men must fight for a future where hope, not savagery, still springs eternal in the human breast.

Like a kind of environmental reworking of Matt Derby’s ‘The Sound Gun’ or Craig Padawer’s ‘The Meat Garden,’ “Missives” takes a military coming of age story and torques it into something absurd–and yet, it remains human and moving. It refuses to play realism’s game, but still offers more of realism’s payoff than most so-called realistic stories.

Brian Evenson, author of A Collapse of Horses and judge of the Omnidawn Fabulist Fiction Prize

About the Author

Reviews

Excerpt

David Armstrong’s story collections are Going Anywhere, winner of the Leapfrog Press Fiction Prize, and Reiterations, winner of the New American Fiction Prize, forthcoming in 2017. Individually, his stories have appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Narrative Magazine, Mississippi Review, Iron Horse Literary Review, Desert Companion Magazine, Best of Ohio Short Stories, and elsewhere. His short fiction has won the Mississippi Review Prize, Yemassee’s William Richey Short Fiction Contest, the New South Writing Contest, and Jabberwock Review’s Prize for Fiction, among other awards. He is a professor of creative writing at the University of the Incarnate Word and lives with his wife and son in San Antonio, Texas.

Missives from the Green Campaign provides glimpses of a world in which the purpose of war is environmental preservation. While many of the rituals of army life remain the same, from hazing to the power dynamics of an authoritarian hierarchy, the conceptual twist of the chapbook is that each soldier must nurture a plant whose survival is intrinsic to his own.

XX-78962

In the new century, it’s terra cotta. It’s ceramic.

Where is your home? they ask us.

In the earth, we respond.

And where is the earth?

In the clay, we say. In the clay. In the clay. Repeating it three times. Planting the idea into ourselves.

At the barracks we sleep in long quonset huts, two rows of cots— heads on the outside, feet on the inside—with an aisle down the center and our footlockers lining the walkway. There is a small window to the left of each bed. Each window is identical: twelve inches by twelve inches of bullet-proof glass. A square foot of sunlight. Beneath each window is a plant, a sprig of green more vibrant than any of our dusty scraps of pixel- lated camouflage. Greener than even the ghillie suits worn by snipers that make them look like sasquatches lying in the bush with their manmade weapons of incredible accuracy.

The ‘houseplants’—though no one here calls them that—beside our beds are varied in species. They are given to us when we first step onto base. Before we receive our uniforms, before we are shorn short, before we’re run ragged through the ringer, before we shed our fat or pack on

our pounds of specialized muscle, before our bodies become homogenized limbs and heads and hearts, there is the Green Room.