Description

Winner of the Omnidawn Open Poetry Prize

Selected by Calvin Bedient

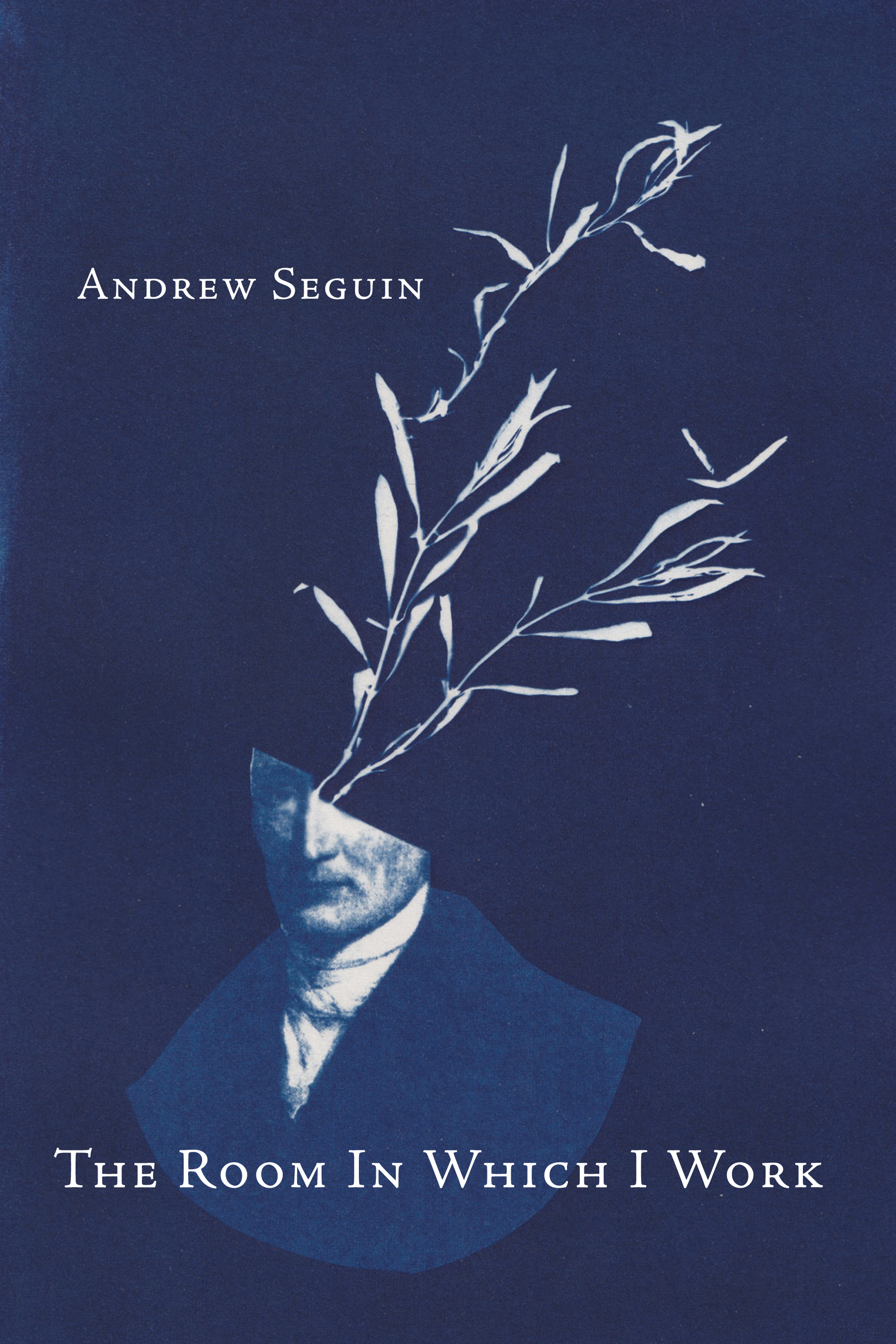

Evoking the life of Nicéphore Niépce, one of the pioneers of photography, Andrew Seguin’s The Room In Which I Work explores how the invention of the medium was also an invention of language. At once biographical and personal, factual and fictional, Seguin’s debut collection not only provides a unique look at Niépce’s life, but investigates how photography has provided lasting metaphors for how we think, write and talk about what we see. Combining original photographs with poems that range through history, chemistry, collage, dialogue and lyric, The Room In Which I Work is a singular meditation on language and image.

In this continually beautiful series of poems, Andrew Seguin possesses and is possessed by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, the maker of the first photograph – a “heliograph” blur-shot of his own dovecote in 1826. Seguin brings Niépce forward in ceaselessly absorbing cinematic close ups with partly researched and partly imagined and altogether wonderful authority. The language is a delight: witness “Rain exceeds its noun by falling everywhere”; “Came clouds / of gunpowder to interrupt / my work.” How rare these days: a whole book brilliant without pretention, reconciling mundanity with the most refined observations, and deeply immersed in utter sympathy and respect for another human being.

Cavin Bedient, judge of the Omnidawn Open

Andrew Seguin has exposed the key elements of photography—light and time—and deftly captured their intersection with poetry. He frames his words with captivating original photographs that harken back to the inception of the medium and one of its inventors. This is a stunning and beautifully sequenced work that will appeal to lovers of words and pictures alike.

Dan Leers, Curator of Photography, Carnegie Museum of Art

Andrew Seguin’s The Room in Which I Work is a remarkably well-executed lyric meditation on the histories, the mechanics, and the poetics of photography, from Niépce’s early experiments with “enabling, or allowing, an image…to paint itself on metal inside a camera obscura” up to the poet’s own flâneur-like wanderings through space and time: “I carry a camera, which is to say I carry a question: what should I photograph?” While many of the poems approximate Niépce’s aim to “copy Nature with the greatest fidelity,” throughout the book Seguin hints at the limits of the photographic medium, often by surpassing them in flashes of pure poetic vision: “the rainbow felt forged / by gods playing horseshoes”; “Off went the crow who had ended // the sentence of the power lines.” Lucid, personal, intelligent, moving, formally astute and supplemented with Seguin’s hauntingly playful cyanotypes, The Room in Which I Work is like no other recent book I can think of, and among the most sophisticated and mature debuts in years.

Timothy Donnelly, author of The Cloud Corporation

About the Author

Reviews

Excerpt

Andrew Seguin is a poet and photographer who was born in Pittsburgh in 1981. He is the author of two chapbooks, Black Anecdote and NN, and his poems have appeared widely in literary journals, including A Public Space, Boston Review, Gulf Coast and Iowa Review. His work often explores the intersection of language and image, and has been supported by the Fulbright Program, the Pennsylvania Humanities Council, and Poets House. Andrew lives in New York City.

A brief interview with Andrew Seguin

(conducted by Gillian Olivia Blythe Hamel)

I was delighted when Calvin Bedient selected The Room In Which I Work as the winner of the 2016 Omnidawn Open. I’d read it in a couple contests in a row by then and had become enamored of its singular coalescence of history, diary, and craft essay within its poetic framework. Every aspect of this work is suffused with the way language filters and shapes our relationship to the visual, beginning with the dialogue that opens the book wherein ‘graph’ falls away from ‘photograph.’ Since you are a visual artist as well as a poet, I wonder if you’d begin by talking about how these two fields came together for you in the formation of this book?

First of all Gillian, thanks so much for these great questions.

I think you are right—and I love how you put it—to start with ‘graph’ falling away from ‘photograph.’ One of the first things I think I learned when studying photography is that the term means, literally, “light writing,” so I have always had that definition in my head, and thought about the ways in which it related to writing, or could itself be a form of writing. When I decided to write this book about Niépce, I realized I had been, for several years, really ambivalent about photography, or at least the use of cameras. I used to always walk around with a camera, making pictures, and I wasn’t doing that anymore. I was making cameraless images and becoming more interested in the history of photography, and other ways of making photographs, and I started to wonder if and how writing poems—which had always been fundamental for me—was replacing the urge I once felt to use a camera. Could poetry do that? What exactly is “that”? I felt that I wanted to go to the source, the first photographers such as Niépce and Daguerre and Talbot, to try to better understand what the impulse to make photographs was at its origin. And in that research I became fascinated with the questions they were asking about language—how were they going to talk about photography, a term that didn’t yet exist in the early 1800s? They didn’t have a vocabulary for this medium, so they had to invent one. They borrowed from other mediums—drawing and painting, for example, and lithography, which had been discovered around that time, and which Niépce studied and was greatly influenced by—and I became even more deeply aware of, as you said, how “language filters and shapes our relationships to the visual.” Especially as I thought about the ways that we, as humans living almost two hundred years after the medium’s invention, use photographic terminology so casually, or metaphorically, talking about “snapshots” of our life, or “cinematic moments” we experienced, or use a new term to describe a partially new practice, the “selfie.” Also—and this comes up in the book—I thought about how photography is replacing writing in some ways, because it is so much easier to take a quick picture of a recipe, for example, with my phone, rather than perform the act of writing it out. I feel a tension there, admittedly, for this visual medium which contains the Greek root for “writing” may be consuming certain aspects of it, and part of me feels there is deep value in the labor of the hand in the act of writing, and part of me loves speed and efficiency. Meanwhile, some of the earliest photographs were of writing—Talbot made an image of a poem of Lord Byron’s, for example! So personally, as a poet and a photographer, this was all very rich material to explore: tracing how the language of photography was affixed to, and influenced, certain ideas about what the medium was, and how that language may have become detached from those referents over time, and of course developed new ones. How does the way we speak about what we see in fact modify or limit what we see? That question is also, I feel, a fundamental question about poetry, and something I am concerned with in my writing.

The impulse to capture or record experience as both an artistic and mechanical exercise is revisited again and again throughout this book; a term that struck me in its multivalent use is ‘value,’ meaning at times either or both the input read by the camera—and, indeed, the eye—to create an image and/or that image or act of recording’s aesthetic worth. And beyond the discussions of visual form, the formal variations within the text itself explore the intersections of this sense of vision in the construction of biography, of lyric memoir, and of the poetic line. How does your impulse to record visually correlate to, or perhaps even contradict, your practice of recording through language—which is, in many instances throughout this book, a recording of a moment of recording—and of aestheticizing and understanding lived experience through poetry?

That impulse is something I think about a lot, and there are deep correlations there, for sure. Photographs, like words, can point to something in the real world, but simultaneously point so many other places too: imaginary ones, abstract ones. I love how a straightforward photograph, say a streetscape made for city surveying purposes, can also feel uncanny, and gesture beyond the façades and curbs it records. There is a similar action in poems. The language we might use to order a pastry can be pushed towards the profound. So that impulse of estranging the ordinary is the same for me, on some level, in making certain kinds of visual work and written work. I am also really curious about the second half of your question, and the ways in which the visual and poetic impulse might contradict. I’m not entirely sure of this answer, but I think that I can feel in myself a desire to make visual work that’s somehow impervious to language, that cannot be described and is bulletproof to words and what they signify, which is something I (and most people, I have to imagine) sometimes find just exhausting. It can be so maddening to always mean something, and for me, making visual work can feel like a release from that, even though I am fully aware that it is not. Especially as I look back and realize that I have worked with books—Moby Dick, the American Heritage dictionary—in recent photographic work.

I’d love for you to talk about the process for creating the cyanotype images incorporated into the book, and which also became the focus of the cover design—again, both the aesthetic and mechanical processes of composition are equally fascinating. How long have you been practicing this particular craft? And in what ways does it complement or differ from your writing practice?

I have been making cyanotypes actively since 2008. In short, the process is one in which iron salts are exposed to ultraviolet light—sunlight—and then developed in water. The process is inexpensive, and easy to do without a lab. Cyanotypes can printed from any kind of negative, be it film, paper, or the direct impression of an object, such as plant material, as Anna Atkins did in her British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, which was one of the first photo books by the way—it appeared in 1843. I made all the cyanotype images in The Room in Which I Work while living in France in 2014. They are portraits of Niépce, and directly reference his materials: lavender, as appears in the cover image, or stone, or his camera. In some cases the stone came from stone I photographed in Rully, France, where Niépce was looking for stone in a quarry, and in some cases I also made the images in that region of Burgundy, the Côte Chalonnaise, where he lived and worked. It was important to me to use the “same” sun that Niépce used in his experiments, and to try to feel his materials, although most of the images were made in Paris. There can be a lot of Romanticism tied up in this way of working, and I tried to embrace it or tamp it down, depending. Making the images was akin to collage—I was cobbling together various elements, such as scanned and printed images of Niépce, plant material, or other related items, and making them into negatives. I would then coat a sheet of watercolor paper with the sensitizer, dry it, place the negative atop it, put it inside a contact printing frame—the pressure of which keeps the paper and negative flush and eliminates any shadow on the image—and expose it in sunlight. The exposures depended on the amount of UV light available, the humidity that day, the density of the negatives, but I would say that most of the images in the book took anywhere from 30 minutes to an hour-and-a-half to print on a sunny day. Then I would wash the prints in my bathtub and dry them. And I feel I should point out that they are a deep blue if you are to see them in person. Maintaining the color wasn’t possible in The Room In Which I Work, which also felt right in a way, as so much of photography, and Niépce’s interest in it, was in the possibility of reproduction.

I think making cyanotypes complements my writing in significant ways; it’s very manual, for one. Coating the paper, drying it, setting up the frame, exposing the print, correcting the exposure if need be—all of these things are finite tasks, whereas poems, and let’s say language, can feel so nebulous, so given to scattering light in so many directions. I think I depend on the balance between the two, although of course, in composing and designing the images, I run into the same scattering of light, as it were, as I do with language. But there is also something mundane about making cyanotypes that I find important: because it’s dependent on good weather, and because it takes hours, when I look at the forecast and see a clear, sunny day on the weekend, I think “Great, can’t write that day!” And that forced release from thinking about whatever poems I am working on is, I am sure, to their benefit.

I’d love for you to talk about any writers, artists, thinkers who have influenced you in this work; in what direct or indirect ways have you felt this influence? And perhaps you could talk about who you’re reading currently? With whom do you feel a kinship, a provocation, a catalyzing relationship of some kind?

The greatest influence was Niépce himself, and his letters, which I was reading and translating while working on this book. I felt a real kinship with him, his voice. I was always amazed at how positive he was, despite being deeply in debt, and despite so many of his experiments failing. He always thought success was right around the corner. And I loved how after he had finished with explaining why some chemical didn’t work, he might tell his brother about how green the countryside was, and how his dogs missed him. For me, there is something really moving in the ordinariness of this extraordinary man.

There are many other writers whose work offered me creative guidance when confronting all this material. W.G. Sebald, for example. His work has always struck me with its singular mix of lyric beauty and documentary, the strangeness of fact and fiction coming together. The way the photographs in his books float in the text, uncaptioned, has always felt daring, because sometimes they seem to act as evidence, bolstering the text, and sometimes I feel they undercut the text, as if they indicate that his incredibly beautiful and insightful sentences are insufficient, we must see what they reference. His books also create a simultaneity of reading and looking, and I begin to wonder if they aren’t the same thing, which I find to be an important state of mind.

I was also reading a good deal of Anne Carson and Cole Swensen before and during the writing of this book, and admiring the ways they beget poetic (and other, sometimes stranger) forms from historical material. In Carson’s books—like Plainwater or Decreation for example—I was also really drawn to the structure of the manuscripts, which encourage disparate forms of writing to coexist. That’s something that I found useful, and which continues to urge me on. I want to read writers that give me permission to be wilder. Christian Hawkey’s Ventrakl has also been a touchstone; likewise Michael Ondaatje’s The Collected Works of Billy the Kid. And because I was not about to live in France for a year without certain writers that always speak to me, I also had the Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens, and the Collected Poems of Robert Frost, and dipped into them regularly. Certain photography critics were essential, too, such as Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag and Geoffrey Batchen, all of whom are quoted in the book.

Lately, I have been reading Lorine Niedecker, Guillaume Apollinaire, Michael Palmer, and Yannis Ritsos. Graham Foust’s latest, Time Down to Mind, really moved me. In prose, I am slowly working through Patrick Leigh Fermor’s books—the Greece ones are up next—and someone who was recommended to me while I was working on this book, Pierre Michon. His “Small Lives” just blew me away—the way he invests lost history with new and imagined life is extraordinary, as are his sentences.

Would you tell me a bit about yourself? Anything you might wish to share that would give a reader more insight into your life and work?

I was born in Pittsburgh, PA, in 1981, the second of four children, and have been in living in New York City since 2003, save for six months teaching English in China in 2005-2006, and the year I spent in France working on this book, which was 2014. Growing up in Pittsburgh, I was really fortunate to go to a high school with a darkroom, where I spent a lot of time from my sophomore year on, and my first contact with photography was marked by contact with, and love for, certain materials—black-and-white film, fiber paper, chemicals such as Dektol and D-76. I think that I could characterize, similarly, my interest in poetry as a relationship with materials that formed around that time. In history class we read Whitman’s “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d,” which memorializes the death of Lincoln, and I remember the music of that title, and the strangeness of the word “dooryard,” transporting me before I had even read the poem. I felt something palpable in those seven words that I myself wanted to feel and make again, even though I had no real understanding of it. So I think that no matter what I do as a poet and a visual artist, my starting point is always the materials, and asking myself, “What are they capable of?”

Evoking the life of Nicéphore Niépce, a pioneer of photography, Seguin explores how photography has provided lasting metaphors for how we think, write, and talk about what we see.

“As a whole, Andrew Seguin’s The Room in Which I Work, is not only an essential historical account of the development of photography but also provides a generous and significant portrait of photography’s astounding inventor.”

I carry a camera, which is to say I carry a question: what should I photograph? Why should I photograph? For many years I never thought this way. I took pictures.

*

It is 1812. Russia hisses away from Napoleon like a fuse, and in Germany the Brothers Grimm publish a collection of tales, which includes the story of a man who learns the languages of dogs, frogs and doves. In the Burgundy region of France, Nicéphore Niépce is searching for stones. There is no such thing as photography.

*

More and more I lift the camera to compose a photograph, my eye flitting through the viewfinder like a dragonfly to find the proper framing, the angle that changes a morsel of the world into a compelling picture, but I do not release the shutter. I am often not able to stand where I want to stand because of traffic patterns, street width, or other circumstances of space, but more often I feel the resulting photograph would have no value, a judgment only the camera can help me to make.

*

The 18th century is turning into the 19th, the ideas associated with photography are floating across continents — does one refuse to light amongst the short-lived clouds of fireflies, or are they all walking back to their studies, saying it smells like rain?

*

“The animals of the mind cannot be so easily dispersed.”

– John Berger

*

Atop Nicéphore’s cane, a dog’s head, carved from bone.