Description

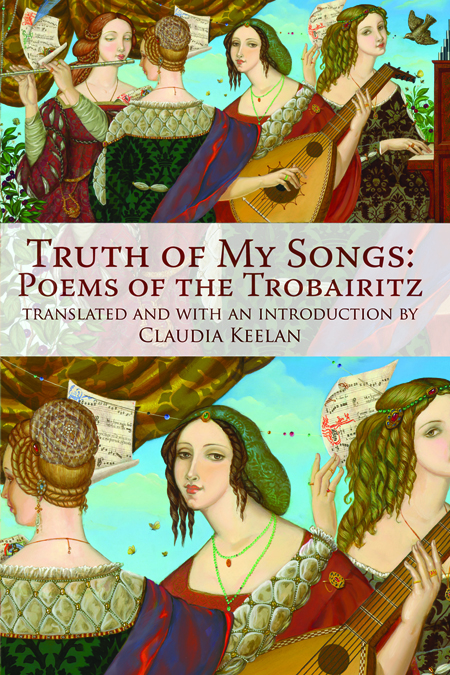

Truth of My Songs: Poems of the Trobairitz is a translation of poems written by the women troubadours, known as trobairitz, whose poems disappeared after the Albigensian crusade of 1129. Together, the poems present a profound argument—for and against—the notion of fin’amor, the pure or fine notion of love, invented by their male counterparts. Tragic, raucous, vulgar, silly, and strange, the poems of the trobairitz prove that women’s history has been recorded since the first women raised her voice and lifted a pen.

With this riveting work, Claudia Keelan makes an invaluable contribution to our knowledge of the trobairitz and their singular work. While the troubadours have been the focus of considerable scholarly and aesthetic attention, their female counterparts are much less known, particularly among contemporary poets. Truth of My Songs opens a wide window onto the ways in which medieval women of this particular class and place managed power and desire—and also gives us an evanescent sense of a dramatically distant world, one with radically different logics, senses, and songs. Through Keelan’s translations and her historically evocative annotations, we get to re-inhabit it in vivid glimpses that defy time.

Cole Swensen, co-editor of the Norton anthology American Hybrid

A miracle that we have the poems of the trobairitz, who wrote poems transforming the means and methods of their male medieval counterparts. Surely here is an initial dropping of the other shoe in the ancient shaky history of gender relations. A further miracle that these poems found their way into the hands of Claudia Keelan, who has written both a daring and exacting translation for our time. Despite/within/out of the strict machinations, constraints and constrictions of courtly love, out of the trappings of the idealized female, inside the mossy walls of the feudal system, somehow, love flourished and flared.What that love was, and how it got played out, comes alive in Keelan’s trobairitz. In these defiant, candid, impassioned lyrics, never before have the trobairitz come so close to us. What a gift that they are here to stay, and thanks to Keelan, will sing their strange, willful, fearless songs long into the centuries before us.

Gillian Conoley, author of Peace and translator of Thousand Times Broken: Three Books by Henri Michaux

Move aside, Arnaut Daniel and troubadours… Keelan rummages in the shadows of the 12th CE Occitan and pulls out the lesser-known but intense lyric poetry of the trobairitz. The brilliance of her translation is in the range and detail of voices, and even as Keelan unearths a category for us we begin to call “trobairitz poetry,” she dismantles it. Aptly, the book opens with a cast of characters, each of whom gets her turn to speak in the book. We see trobaritz-poets as real women—they know the rules of the game, the conventions of courtly love, and its language of religious allegory; and they subvert this framework. Aware of their positions, troubled by its fictions, they are still passionate for ideal love. This is more than “attitude” — it is rebellion, the trobairitz risks their lives in a constrained social system. Keelan captures the spirit of this rebellion by drawing from the world of rap, and the slang she uses makes this poetry raw, and live, and now, when really, the truth is still the same for women.

Mani Rao, translator of Bhagavad Gita: A Translation of the Poem

About the Author

Reviews

Excerpt

Claudia Keelan is the author of six books of poetry, most recently the verse drama O, Heart (Barrow Street, 2014). Her honors include the Beatrice Hawley Award from Alice James Books (Utopic 2001) and the Jerome Shestack Prize from the American Poetry Review in 2007. Truth of My Songs: The Poems of the Trobairitz is her first book of translation. She is Professor of English and Director of Creative Writing at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, where she edits the literary annual Interim.

A brief interview with Claudia Keelan

(conducted by Rusty Morrison)

It is such a pleasure to see this book come to fruition! I believe it was in 2009 that you first spoke to Ken and to me about your intentions for this project: to produce a translation of the 12th century women troubadours, the trobairitz—women who were able to manipulate their male-ascendant structure to express their own intimate and even subversive concerns, rather than let their voices be manipulated by the form’s dominance. Ken and I were immediately excited—we realized how valuable this work could be to modern readers, since so many of us today are looking for ways to recognize our own agency and empower ourselves within the many hierarchies of overwhelming authority in which we find ourselves constrained. But I can only imagine how daunting the work must have been. I want to ask you so much about the project, your process, and its impact upon you. Let’s begin simply: Can you speak to how the idea came to you and what were the first poems you translated?

I was living in Denver rather suddenly, after having met and married Donald Revell. One of his students, Carol Nappholz, was just finishing her dissertation “Anonymous Women: The Female Voice in the poetry of the Troubadours.” Like most people, even now, I’d read the troubadours, but hadn’t even heard about the trobairitz. Carol’s book focused on poems in the troubadour’s oeuvre that spoke in women’s voices. Scholars were debating—and continue to debate—how many of the anonymously written poems could be unqualifiedly attributed to women writers, as so much of what we know about the trobairitz is found only in the vidas—or biographies—of the troubadours. Meg Bogin’s 1976 translation of the trobairitz was the first book in English that introduced the 20-something women who are indisputably trobairitz. Carol gave me the manuscript and said “make this into poetry.” Twenty years later, I translated a sirventes, a debate, or protest poem in one voice. Called “I Grew Coarse” in my translation, the poem protests the sumptuary laws controlling women’s clothing. I was a visitor at the University of Alabama at the time, living again in the south, where social relations still seem strictly prescribed by evangelical Christianity, even while date rape is rampant. So it was somehow inevitable that I’d start with the protest poem, even though they are rare in the Trobairitz’ corpus—there are two, and both are anonymous. Most of the poems are tensos, a poem in two voices that argues about various things, but mostly love, the fin’amor of the troubadour tradition, the so called fine or pure love invented by the troubadours, to woo his lady, who is the feudal lord’s wife, and a trobairitz. Some readers have associated me with the L-A-N-G-U-A-G-E movement, but it’s an inaccurate association, as my interest has always been in the lyricism, the music that is the materialism, of language.

You are a poet with an excellent ear for the music of lyric poetry, a wealth of critical experience in the history of lyric writing, and you are much-respected as an innovative writer who is able to use language to attend to its ambiguities, even as you tenaciously examine our human enterprise. Can you speak to the challenges in bringing this work into a more current idiom? I know that you speak with depth and candor about this process in your text’s introduction, but can you give us some sense here of what was most rewarding, exciting, and challenging to you in this work?

Thank you, Rusty! The methods I’ve developed as a poet, and the attention I’ve given to what you call “our human enterprise” has been to put the gaze on the one and the many, and their intersections. The longer I listened to the poems of the trobairitz, the more I could hear that same dynamic at play. The trobairitz, the lady of the troubadour’s attention, didn’t particularly enjoy the categorization that fin’amor placed on her own self, and on her life. Marriage in itself is viewed with anger, resignation, sorrow, rarely, if never, with joy, in their poems. Centuries before the women’s movement called attention to the commodification of women, and the dual cooption of feminine authority imposed by marriage and children, the trobairitz were arguing, lamenting, resisting, these same things. They are very aware of what their actual conditions are, over and beyond the fictionalized lady of the troubadour tradition, and also what they received from this tradition, and from the feudal system by which their marriages are bound. They realized they were not free, much less loved or respected, within a system that nonetheless insures their relative wealth and mobility. In that sense, they are modern. Once I really heard that, all I had to do was transfer it into contemporary language, which wasn’t too hard, since the kind of human unhappiness they experienced is what comprises the unhappiness of the status quo, or what in our country was once called the middle or upper middle, class, whose material wealth didn’t translate to personal happiness.

I know that you traveled in conjunction with and to augment your research. How did visiting sites in Europe impact this work? What moments were most memorable in their influence upon this translation? Can you narrate for us any instances of surprise, of challenge that seeded work in this text? What experiences were, and/or remain for you, most resonant? Do you feel this translation is more alive to the trobairitz because of that travel, because you invested that time? In what ways? And/or were the changes more subtle than can be clearly articulated?

Long before I read the trobairitz, I had been fascinated with the heretical Christians called the Albigensians or Cathars, who were slaughtered by command of Pope Innocent the 111 in 1129, an early crusade made largely to gain possession of the land of the large fiefs in Occitania, what is now called the Pays D’oc, or the south of France. After the crusade, Catharism disappeared from France, and the trobairitz and their poems were never heard of again. It is very likely that many of the trobairitz were Cathar, and were either killed or silenced during and after the Albigensian crusade. So, along with the extinction of a liberating Christianity, came also the extinction of the first known instance of sustained women’s writing. I travelled to the Pays d’oc, to Albi, and while there, I wandered into the city hall of the town, where hung an amazing painting called Femmes des Albigenses. It depicts a group of semi-naked women, all of whom would be killed that day or the next, confronting the crusaders. This willingness to live and die for a lived belief parallels certainly the clear pinnacle of fin’amor, where lover submits to the higher authority of the lady, and lady, if she hears the truth of his song, too gives way.

I have heard you speak thoughtfully about your own writing process. If I’m recalling correctly, I understand that you may, before writing, find yourself musing, meditating on an energy or idea, but that once you begin to write, you move through the work and then complete it. In other words, you are not a poet who actively or consistently engages in extensive revision as part of your writing practice. Is this still true about you? And, did you use this strategy in your work of translation? Or did you find yourself returning, revising, in ways that might be different from your own creation of poems? Or was translating this work a hybrid of practices?

Some of the translations came through in one piece. Others took longer, usually because they were longer. You’ll notice that some of the tensos are several pages long. Ultimately, though, after I heard the translation and wrote it down, very little revision was done.

Did your process change from one trobairitz to another, were some of these women closer to your process, and some more different, and thus asked different process strategies from you? Can you speak to their differences and how that impacted your translation process?

My process didn’t change, but I was very aware of the differences in personality of each, because they made themselves very clear. Countess of Dia, for example, laughs through her poem, making puns, accusing mockingly, while Castelloza speaks through heartbreak so great, I too cried when I translated her. Each of the trobairitz speaks with a vivid individuality, even as they employ the conventions of courtly love. The trick became how to translate the essence of their individual feeling.

Who are the authors with whom you feel a kinship? Who influenced you in this work of translation? Who are you reading currently?

Oh my goodness, so many! Those who follow a trajectory of negative capability. Some would include William Blake, John Keats, Arthur Rimbaud, Walt Whitman, Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, William Carlos Williams, George Oppen, Lorine Niedecker, Louis Zukofsky, Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, Theodore Roethke, James Wright, Adrienne Rich, Barbara Guest, Bernadette Mayer, Susan Howe, Alice Notley, Brenda Hillman. All of my writer friends. These are just the poets. I love philosophy, though it is slow going. Lately I’ve been working through Levinas again. Last year Whitehead.

Pound’s theories of translations helped me to my method, as did Louis Zukofsky’s Catullus, David Slavitt’s Virgil, as they too were translating a vastly older text, and found the means to carry across—the first meaning of translation—lost languages into a contemporary idiom. After I had translated the poems, I was also interested to find that both Pound and Snodgrass translated troubadour poems via the jazz of their periods. As my translation sometimes involves rap and hip-hop in vocabulary, idiom and rhyme, I was glad to see that others had found the music of their moment an apt vehicle for the troubadour’s vernacular poetry. I read Derrida and Venutti, among others, also in the process of translating the poems.

Right now I am re-reading William James’ Pragmatism in conjunction with Stein’s “Stanzas in Meditation” and doing a thorough reading of Robin Blaser’s complete work, both for independent studies with students. Also, Native American Oratory and mythology. And Alan Watts’ autobiography.

Would you tell me a bit about yourself? Anything you are willing to share that might not be in your short bio that is published in the book?

I try very hard to believe that life is beautiful, and that things make sense, and am almost constantly heartbroken when the evidence shows otherwise. My poetry and my teaching are rooted in the practice of fair-mindedness and equilibriums. When I’m alone, it’s hard to maintain either. I wish I had more friends I could see on a daily basis, who could either razz me out of my sadness, or sit with me and weep. Or we could just look at the sky. It amazed me how companioned I felt when translating these poems. I felt I’d found lost sisters. It was a happy few years.

You were actively involved in the selection of the image that is used in the cover design for this book. Would you describe the search, your hopes for the cover image? How this cover may fulfill your desires, intentions?

Well, it is beautiful, yes? It reflects an idealized state, one that doesn’t vie with the history of the period, but does mesh with an idea of harmonious love and music making, which was at the heart of the story the troubadours told themselves about their art and times. Friendship was a very important ideal in the troubadour’s lexicon, and while there is evidence that the male poets did make and keep friendships, there isn’t much record of women’s relations to each other during the period. The cover elicits friendship and ease. I go with that.

The trobairitz navigated claustrophobic restrictions caused by gender, audience, lauenziers (gossips or spies), repetitive poetic conventions, and the religious and cultural context of their lives. Yet despite this they burst forth with hilarious and heartbreaking poems of exquisite sophistication, inspired by what Keelan calls the “power within powerlessness.”

These exuberant poems often challenged the church’s position about sex and procreation. Good for them, says Keelan, whose thoughtful book suggests that even today the trobairitz offer a perspective that needs to be heard.

Centuries before the women’s movement called attention to the commodification of women, and the dual cooption of feminine authority imposed by marriage and children, the trobairitz were arguing, lamenting, resisting, these same things.

Is You Is, Or is You Ain’t My Baby? Finding the Trobairitz

It took me 20 years to start this translation. I needed the distance age brings to questions of love, I suppose, to begin. To translate the women troubadours, known as trobairitz, I knew I had to somehow gain access to their experience, which is believed to be the first sustained, cultural instance of women’s writing. To start, I had to find a way to hear their voices, over and beyond the somewhat repetitive and stylized surfaces of the poems’ conventions. Too, as women and poets, the trobairitz were intensely aware of their audience, all whom were members of the feudal courts to which they were bound by marriage, and so translating them involved understanding the complexities of the society in which they lived and wrote. Listening to the trobairitz’s poems, I heard girls arguing with themselves, and with their lovers and their friends. Their poems argue for and mostly against the assumptions of what is called romantic love, the system of patronage by which they were bound. It is true that fin’amor was a notion of love invented by men involving chivalry to women in order to be better regarded by other, more powerful men; codes that continue still to influence representations of women’s identity.

So why translate the poems of 12th-century teenagers? There is something very moving about the drama and extremes of adolescence, a drama that is made melodramatic now by the film industry and television, even as much of the contemporary mind is still acting out Romeo and Juliet. Teenagers are comfortable with the extreme, which is good, because they are usually pretty powerless, despite the power of youth’s attraction, to determine the way things go, even as our culture is obsessed with youth to the extent that many of us will die before we grow up. Popular music often plays to a sense of immediacy, of urgency, and often to a powerlessness regarding love, which is strongest when you’re young. It helps to remember that childhood is an invention of the modern period, and that the teenagers writing these poems were women in their time, which was not a particularly good time to be a woman. Women, in the eyes of the Catholic Church, were equal to men with respect to grace and salvation, but unequal in interpretations of the creation myth and original sin.2 If a woman did not produce children she could be returned to her parents, or be put into a convent. The trobairitz’s oeuvre speaks both to urgency and to the power of powerlessness, sometimes sarcastically, sometimes in anguish, and mostly opposing the fable of purity embedded in a poetic system derived by men. The poems also contain recognition of their unlikely power, which is the power of the constructed ideal, one continuously derived from the ongoing drama of women’s history.

The troubadours who defined this code of chivalry called it fin’amor, or “fine love,” wherein the troubadour pledges obedience to a woman of noble birth, paying homage to her in songs where the explicit reward is simply that he is “made better” by the exchange. The trobairitz were, in fact, “the lady” of troubadour lore: 20 or so aristocratic teens, active from the mid-12th to the mid-13th centuries, who wrote poems which are the first recorded instance where “the lady” speaks back. The ingenuity of the troubadours cannot be overestimated. How better to secure a place in the feudal hierarchy than to invent a system of exchange that places the woman in ideal high regard? Scholarship in the latter half of the 20th century has established that courtly love was essentially “a system men created with the dreams of men,” not women, in mind. Their ingenuity cannot be reduced so simply, however, as we still have not sufficiently answered the question of how such poetry came to be. That the troubadours created the unlikely tradition of fin’amor in a period rampant with misogyny is remarkable in several ways. By associating an earthly woman with an ideal of purity, they were making a religion of love, which was tantamount to blasphemy. By turning their songs into performances that were sung by joglars, or actors at court, they were ensuring their economic reality. Borrowing in part from the Catholicism they openly despised, the lady in late troubadour poems was often read as a manifestation of the Virgin Mary, whose intrinsic purity cannot be tarnished, even by childbirth.

On the other hand, being “made better” by a beautiful woman can be expressed in vastly sexual terms, and often was in poems that are as equally ribald and profane as those apparently devoted to Mary. The lady would be chaste, yes, but what was the harm of insinuation if the situation was right? Their poems are full of senhals, or code names, an indirect address that supposes the troubadours could be speaking to any woman in the room. Thus, the provisioning of the sacred and profane is always in dialogue in the troubadours’ system. Since women scholars in the last and present century have begun scholarship concerning the troubadour tradition, especially in regard to the trobairitz’s resistant response to themselves as the idealized lady, the narrative of the phenomena has changed. C.S. Lewis, for one, saw the vassalage of the troubadours to the lady as a psycho-spiritual response of the unaccommodated, mostly unmarried, transient troubadour. Medieval marriages certainly had nothing to do with love and everything to do with matches of interest, i.e., the lady was of interest as a piece of property to her husband (if not a “sack of dung,” which was a common epithet for women in the period). Pursuit of sexual pleasure was sacrosanct, as passion, or desire, was evil and a result of the Fall, even in marriage, where sex’s function in the eyes of the Church was solely to produce progeny. The troubadours’ oeuvre was therefore heretical because they placed fin’amor above all other duty. Instead of children, true love produces joi—which is what both love and the poem seek in the lexicon of courtly love.

So for many earlier scholars, the troubadours’ elevation of the lady—over and against the utilitarian—was a social and spiritual rebellion, a “new feeling” that contained humility, courtesy, adultery, and the Religion of Love, i.e. romantic love, all in a period where none of these attributes were particularly manifest. The troubadour is the uber rebel-heretic—poet(!)—humbly and courteously committing adultery with his lord’s wife, in homage to a religion of love, which prior to this brief period in Occitan had not been seen before. I have always loved this narrative, because it aptly demonstrates the emergence of the new as both homage and rebellion. The voices of the trobairitz work the extremes of love embodied in the ideal of fin’amor, presenting a body of poetry that questions and critiques the basic assumptions of courtly love. Intensely aware of themselves as the subject, many of the trobairitz’s poems debate the issues of purity associated with the Beloved in the troubadours’ poetic oeuvre and raise questions of love, power, economics, religion, and political affiliation in gender relations. Even now as the Republican party continually strives to regain control of women’s bodies in the US; in the sobering fact of women’s poverty worldwide, and in the staggering number of violent crimes against women everywhere, the trobairitz’s powerfully defiant poems remind us that the his in history has been questioned for centuries.